Soon-to-be saint Titus Brandsma wasn’t perfect, but did inspire many

-

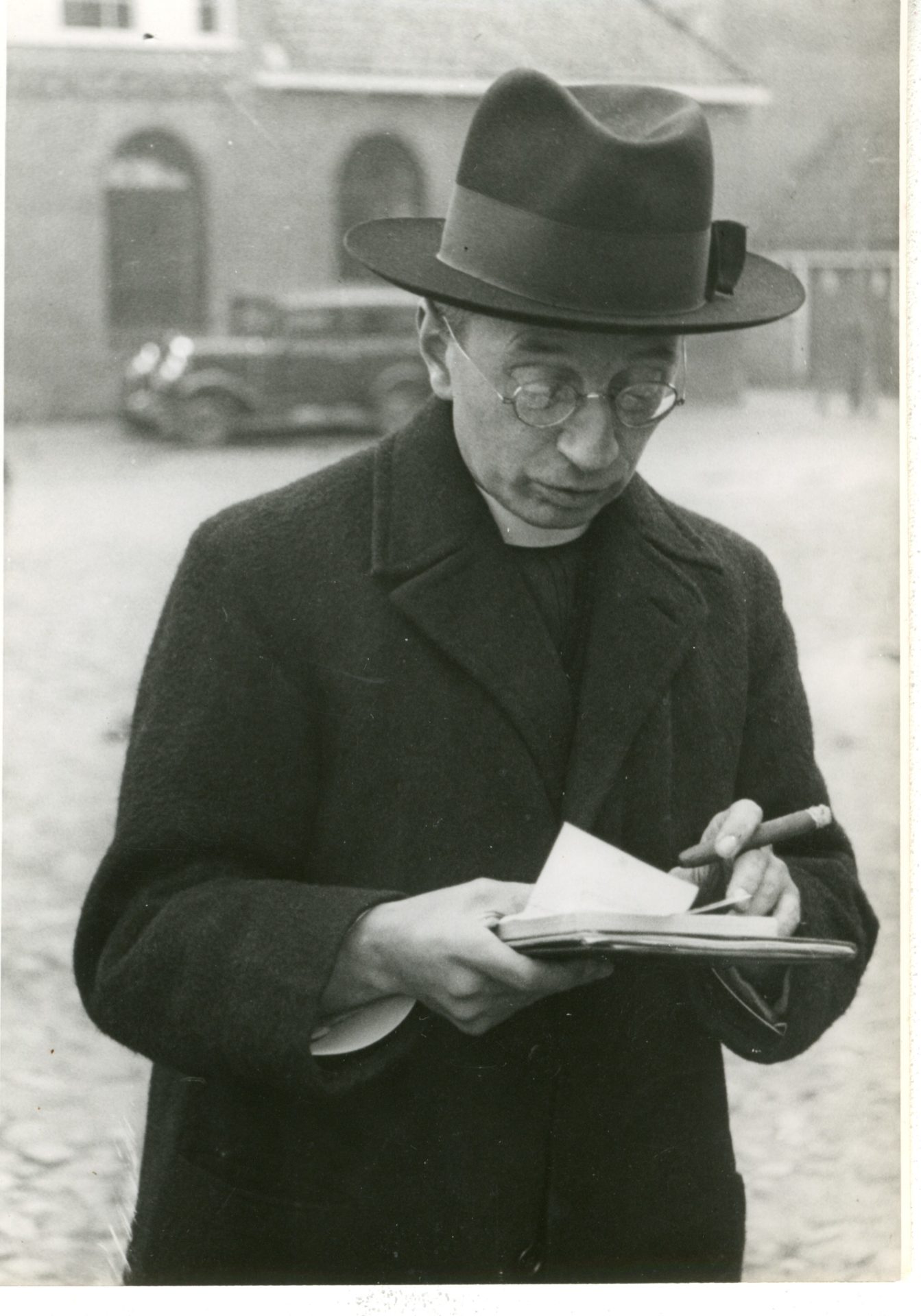

Titus Brandsma. Photo: NCI.

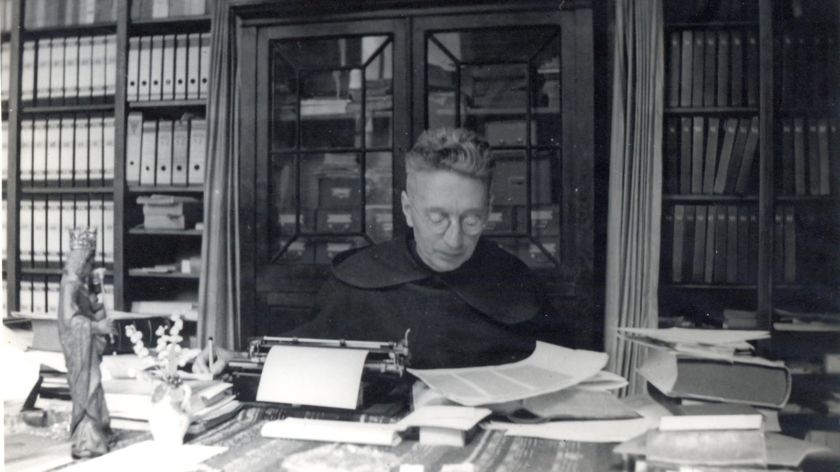

Titus Brandsma. Photo: NCI.

This coming Sunday, Titus Brandsma will be canonised by Pope Francis during a Mass in Saint Peter’s Square in Rome. The former Carmelite priest, professor and rector of the Catholic University Nijmegen who died in Dachau was not perfect, but he was an example to many. ‘He was a virtuous if fallible man.’

19 January 1942. Officers from the German Sicherheitsdienst (SD) knock on the door of Doddendaal monastery in Nijmegen. Earlier that month, the SD office had been tipped off about a Carmelite priest and professor of the Catholic University Nijmegen visiting Catholic newspaper editors.

The aim of the 61-year-old Titus Brandsma’s visits had been to persuade the editors-in-chief to not include any advertisements for the collaborationist NSB party or organisations affiliated with it in their papers. As it turned out later, Brandsma’s critical lectures on Nazism were also included in his SD file.

Potato crate

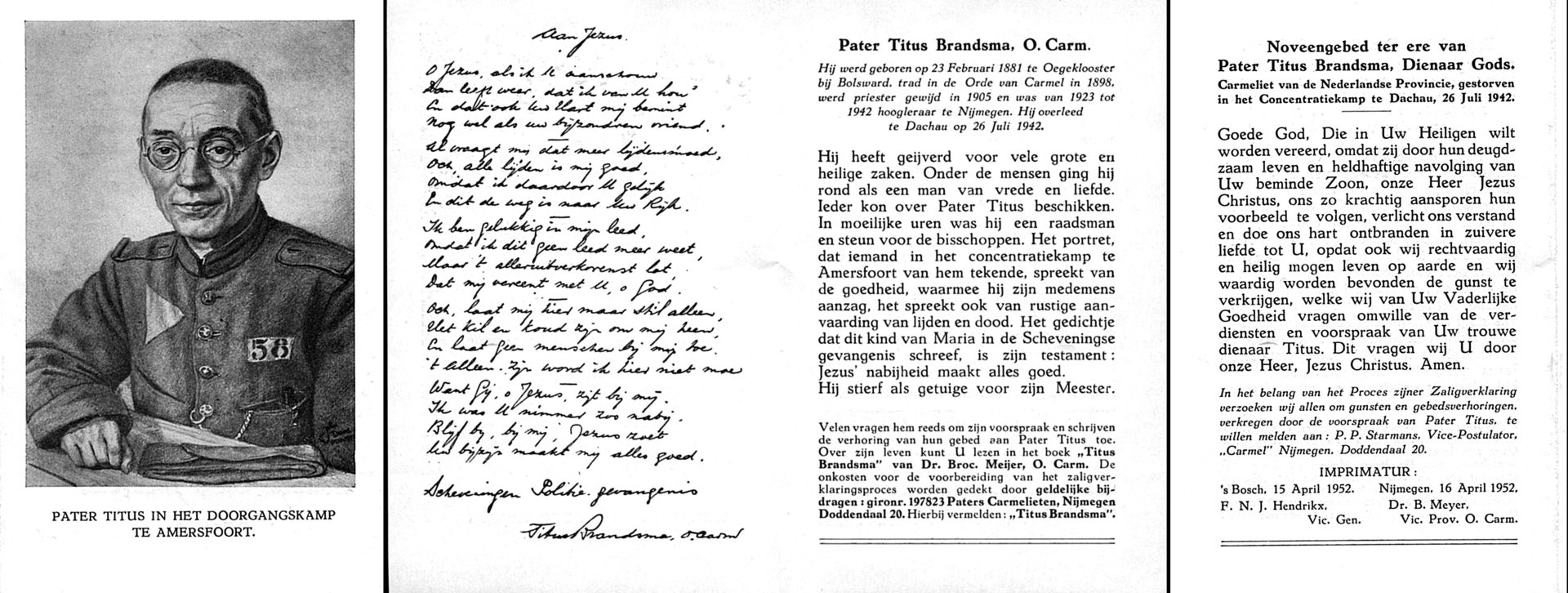

Brandsma did not resist arrest. The Germans took him to the prison in Scheveningen, where he was interrogated by SS officer, Paul Hardegen. Brandsma said he had nothing against the Germans as neighbours, but was against a political regime that was rooted in another country.

On 12 March 1942, the Carmelite priest was transferred to the Amersfoort labour and punishment camp. He gave a lecture from atop a potato crate on Good Friday about how medieval man, at the mercy of natural disasters, could still be touched by sin or spiritual ecstasy. The lecture by Brandsma, who had already lost a huge amount of weight, made a profound impression on his fellow prisoners.

After another interrogation in Scheveningen and a short stay in Kleve transit station, Brandsma was transported by prison wagon to the Dachau concentration camp, some 20 kilometres north of Munich, on 13 June. The hard labour, abuse by the occupying forces and poor hygiene soon proved fatal to the already weakened Brandsma. He ended up in the infirmary, where he died on 26 July.

Anno Sjoerd

Next Sunday, Titus Brandsma, born Anno Sjoerd Brandsma in the Frisian town of Bolsward in 1881, will be canonised alongside nine others in St Peter’s Square in Rome. The Mass will be conducted by Pope Francis in St Peter’s Basilica, and St Peter’s Square is expected to be filled with believers from all over the world. A delegation from Radboud University will also be present in Rome. What was Brandsma’s time in Nijmegen like?

The Carmelite priest first lived in a house on Kronenburgersingel, together with others from his monastic order, the Carmelites, who were studying at the brand new Catholic University, and later at the newly built Carmelite monastery on Doddendaal. Since its foundation in 1923, Brandsma was employed by the university (now Radboud University) as Professor of philosophy.

‘The ministry did not take Ferdinand Sassen’s tax advice well’

Things could have gone differently, says Professor Emeritus of Ecumenics, Peter Nissen. ‘Jos Schrijnen, the first rector magnificus of the Catholic University Nijmegen, thought someone else would be better for the philosophy course,’ he says. ‘Namely one Ferdinand Sassen, a priest and philosopher of some standing in academic circles. But Sassen had published some tax advice that did not go down too well with the ministry, and he was discredited as a result. Schrijnen thought, we cannot get him involved or else we will have a riot on our hands. Non-Catholic newspapers would exploit this fact.’

Huge publication list

This opened the way for Brandsma, who had obtained a doctorate of philosophy in Rome and taught the subject in the Carmelite study house in Oss. The fact that Brandsma belonged to the Carmelite community played to his advantage, says Inigo Bocken, an academic staff member with the Titus Brandsma Institute, who is working on a new, intellectual biography of Brandsma. ‘The bishops who founded the university wanted to have as many orders represented in the teaching staff as possible,’ he says. ‘It was also important that the university didn’t have to pay priests’ salaries. But, based on the correspondence I was able to look into, I suspect that they had him in mind for a professorship in Mysticism and Spirituality anyway.’

The unlucky Sassen was never able to come to terms with the fact that he was passed over for the Philosophy professorship when the university was founded. Bocken: ‘He reproached Brandsma in an article published in De Gelderlander in 1939 for not doing more serious academic work. But Brandsma wrote an awful lot of popular articles that appeared in a wide variety of magazines. For example, he wrote 200 articles for De Gelderlander based on solid research. His list of publications is enormous. I sometimes wonder where he got the energy from.’

Frisian Nature Conservation Association

Still, Sassen’s reproach of Brandsma is not entirely misplaced. Brandsma was always known more for his social engagement than for his intellectual merits, Bocken explains. ‘His colleagues sometimes commented on him neglecting his duties as a professor because he founded so many associations. To give two examples, he was a board member of the Catholic Esparantist Association and the Frisian Nature Conservation Association.’

According to Nissen, Brandsma saw academia very much in the context of service to the Church and society. ‘Even today, academics are often told that their knowledge has to be shared and disseminated as much as possible, but you don’t see it reflected in the management of the university,’ he says. ‘Those who publish internationally and bring in vast amounts of research money are considered the most successful. But Brandsma was a completely different sort of academic. His merits mainly lay elsewhere.’

‘Brandsma wrote groundbreaking articles’

Brandsma’s contributions to philosophy were modest, but this was a different matter for mysticism, says Bocken. ‘He did write groundbreaking articles in academic journals dealing with medieval piety and modern devotional studies. He was a sound academic who had a vision of what his profession should be.’

Dies lecture

His most important academic text, where all his publications come together, was delivered by Brandsma as rector magnificus in the 1932-1933 academic year, on the university’s anniversary. In his speech, Brandsma called racial doctrine and totalitarianism a ‘kind of filler for the void that has arisen in many people’s lives as a result of the loss of religious consciousness’. Bocken: ‘He was early to denounce it, more than five years before the outbreak of the Second World War.’

Brandsma identified a social-spiritual crisis in his dies lecture, Bocken explains. ‘He did not say that people did not believe any more: according to Brandsma there was enough understanding of God. But he felt communism and fascism also had concepts of god, although abstract, and these attracted a lot of people. According to Brandsma, mysticism and spirituality could help people to adapt the concept of god to the times.’

‘Today, as a society, we do not know how to deal with questions of salvation’

According to Bocken, Brandsma wanted to use his lecture to show how people should deal with important concepts, such as religion. ‘Mysticism points out that this search is new and different for everyone. Today, as a society, we do not know how to deal with questions of salvation, life and death. People need guidance. I think it is a beautiful idea, and one that I have seen in few other thinkers.’

Blemishes

In the Catholic world, there is a tradition of hagiographies or saints’ lives: honeyed tales in which saints are literally praised to the heavens. For example, it was written of Jan Berchmans, the Flemish saint and namesake of the Berchmanianum, that he refused his mother’s breast on Good Friday because he wanted to fast. Brandsma, on the other hand, does have some blemishes. In the Brabants Dagblad, he called him ‘a fallible yet virtuous person’.

Brandsma, like many other Catholics in the 1930s, was a supporter of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. ‘Let’s be clear: Brandsma was opposed to any kind of totalitarian system,’ clarifies Nissen. ‘He wanted nothing to do with Russian communism, nationalism or Mussolini. In Franco, he likely saw someone who wanted to restore the old monarchist authority contrary to the Republicans. Moreover, the Republicans had murdered a number of priests. It was not yet clear that Franco would become a dictator. It is easy to judge in hindsight.’

Brandsma was also not unfamiliar with other prejudices that were widely shared in contemporary Catholic circles. ‘You can find this out about him if you look carefully in his newspaper articles and letters,’ says Nissen. ‘For example, that Jewish people did have a lot of influence in the economy and in world politics. First and foremost, Brandsma was strongly opposed to any violent action against them, as well as to racial doctrine and national socialism. He gave his life for this conviction.’

‘Patron saint of journalism’

Pope John Paul II beatified Brandsma for his martyrdom in 1985. Brandsma still had to pass an important hurdle for canonisation: a miracle had to be attributed to him. That came in December 2020, when a commission of doctors declared that the healing of American Carmelite Michael Driscoll was medically inexplicable based on a 1,600-page report. In 2004, Driscoll had an aggressive cancer with metastases in his lymphatic system, but he recovered. A group of theologians established that the healing was due to the veneration of Titus Brandsma.

Nissen is not a fan of the system of canonisation based on miracles because medical miracles can be disproved by science years later. ‘What was a medical mystery thirty years ago may not be the same thing today,’ he says. ‘Moreover, it distracts from the crux of the matter. Saints are people who were fundamentally virtuous.’

‘I am constantly amazed by how many people venerate Brandsma in the most secular country in the world’

The religious academic thinks that Brandsma could be a saint who appeals to many people outside of Catholicism. ‘Freedom of the media and freedom of newsgathering are very topical subjects. Brandsma would certainly have opposed the muzzling of the media, as is now happening in Russia. The bishop of den Bosch, Gerard de Korte, also once said that Brandsma would be an ideal patron saint for journalism.’ Inigo Bocken agrees with this sentiment.

Bocken sometimes receives letters from people who say that their parents knew Brandsma. ‘He would have visited their parents back when they were toddlers themselves,’ he says. ‘I am constantly amazed by how many people venerate Brandsma in the most secular country in the world, even before there was a canonisation.’

Absent-minded professor

Titus Brandsma was quite popular with students, but not because he was a good lecturer. ‘Students did not find his lectures very interesting,’ says Peter Nissen. ‘It didn’t help that he was very absent-minded.’

The religious academic illustrates his observation with an anecdote from author Godfried Bomans, one of Brandsma’s students. ‘In breaks between lectures, students and professors would walk around the gardens. Brandsma, smoking his pipe, asked Bomans what he was studying. ‘Absolutely nothing,’ replied Bomans, but Brandsma had completely missed the point. ‘A nice subject, but then we also have to act, don’t we,’ Brandsma replied.

The distance between students and professors in the university’s early years was relatively small. ‘For many students, Titus was a kind of unpaid student pastor,’ says Nissen. ‘When students came to him with problems, he would respond to them. This was often at the expense of his free time and health – and perhaps at the expense of his lectures too.’