Summer interview (4): PhD student Islamic Studies Maria Vliek

-

Foto's: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Foto's: Erik van 't Hullenaar

The attacks on London, Manchester and earlier this year Paris and Brussels are the work of Muslim terrorists. Always those Muslims, you hear people sigh. What does PhD student of Islamic Studies Maria Vliek (29) think about it? She worked for three years in Mombasa, where such attacks were a daily occurrence.

The port of Mombasa, 2012. Maria Vliek is perusing a file when her boss storms in. He is enraged. Another attack in a church, on a market, at a school or in a disco of his city. The Al Qaida-affiliated Somalian extremist group Al-Shabaab is overactive in Mombasa in those years. Precisely the period during which the Twente-born Maria Vliek works for a large transhipment company in the harbour city. She has been assigned to corporate social responsibility, the charities supported by the company: hospital wings under construction, schools, that sort of thing. Back in the Netherlands, she will write about these attacks in her Master’s thesis. A depressing list: fifteen pages in five years’ time.

No wonder her parents were not enthusiastic when she left for Kenya after her Bachelor’s in English Language and Culture, because she’d had enough of studying and of the Netherlands. Nor did it help that her parents had never met the English friend she was going to help with his volunteer organisation in that country.

‘Hand grenades were thrown into the club’

Her time in Kenya was certainly not dull, says Vliek looking back on this period. ‘At the club we always went to, one day hand grenades were suddenly thrown inside. That was very scary.’ She ended up working for a transhipping company in Mombasa for three years. The owners, a Muslim family, received her with open arms. Always friendly, helpful, hospitable. Vliek had never seen her boss as angry as he was that morning. ‘Maria’, he snorted. ‘The Quran says you are not even allowed to take your own life, let alone someone else’s!’

Al-Shabaab

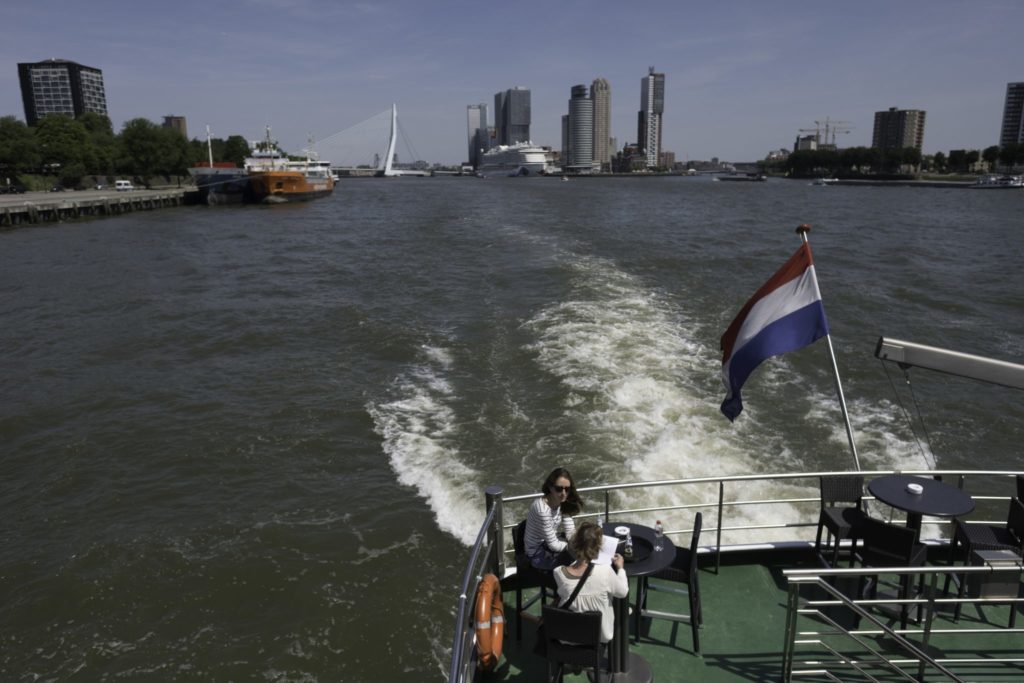

We sail through the port of Rotterdam, Vliek’s current place of residence, where she has settled with her soon-to-be English husband. Just as Mombasa, Rotterdam is multicultural and internationally oriented. With the difference that there are many more Muslims in Mombasa. Half the inhabitants there are Muslims, the other half Christians. With its attacks, Al-Shabaab tried to drive a wedge between the Christians and Muslims in the city. To no avail, noted Vliek at the time. ‘The people I spoke to always said: “This is the work of Al-Shabaab; they are not Muslims.” The attacks were politically driven; they had nothing to do with religion. The Muslims said so, but so did the Christians. They also said: “This is not Islam. We’ve been living together peacefully for thousands of years.” No matter how hard Al-Shabaab tried, they never managed to tear the community apart. I found this truly remarkable.’

Vliek notes that the attacks of extremist Muslims on Manchester, London and other big cities are disastrous for the reputation of Muslims in Europe. Muslims are often viewed with suspicion. This doesn’t serve anybody she says. On the contrary: it only increases the frustration that seems to play a role in the radicalisation of young people. ‘People are so much more than their religion. But this us vs. them attitude is truly the most harmful thing. It makes it difficult to maintain an open dialogue about a topic such as Islam in the Netherlands. People often ask me why young people radicalise. Many theories have been written about it, which focus on marginalisation, racism, masculinity, ideology, religion, culture. So many factors play a role. But not everyone is willing to recognise this complexity, and people are quick to label.’

Fear of globalisation

The 29 year-old PhD student looks on as the touring boat makes waves on the Maas. A city like Mombasa is probably more resistant to religious conflict, says Vliek, than most Dutch cities. Mombasa has a long history of trade and migration. As early as the sixth century the island was already trading with China and India and it was conquered consecutively by Africans, Persians, Omanis, Arabs, Jordanians, Portuguese and Brits. The local religions have co-existed for centuries and fought out quite a few religious conflicts. ‘I think that therein lays their power. The city has built up resilience against religious conflicts that we can learn from. In our country Muslims have only recently become a large minority. The fear of globalisation that you can now feel in the Netherlands is something of the distant past for Mombasa.’

‘The fear of globalisation you now feel in the Netherlands is something of the distant past in Mombasa’

Back in Groningen Vliek studied Religion, Conflict and Globalisation. She wrote a Master’s thesis on how young Muslims in Kenya define their identity. And the role of religion in this process.

On the port side we now see SS Rotterdam, ’the largest passenger ship ever built in the Netherlands’, says the announcer. Vliek does not hear it. She is thinking about our latest question: why would a pragmatic Twente girl become so fascinated with how Muslims experience their religion? Her PhD is also about this topic. She interviews people who have left Islam behind, and who are going through a difficult process of doubt and sometimes hard confrontation with family members and the Muslim community.

Guide

‘I’ve always found religion interesting – I was brought up Protestant – but my interest really grew in Mombasa. There I saw what religion can mean to people. The Netherlands is a very secular society: we practise religion behind closed doors. Things are very different over there.’ In Kenya, religion is more visible, in clothing and in behaviour. People constantly refer to God in their daily speech. For example, when Vliek left in the afternoons to go home her colleagues would always say ‘God Bless’. ‘There religion is not just something you do on Sundays. It defines how people live, how they deal with each other. Many Muslims I met use their religion as a guide through life.’

She gives the example of her former boss who spent so much of his money on schools, hospitals and combatting poverty. ‘He was incredibly involved in the community. And I think this certainly had to do with how he experienced his religion. I don’t think he saw it as his duty to care for others, but more as something that as a Muslim you do as a matter of fact. Of course not everyone is so involved in the community, but I did see a lot of it in Mombasa.’

Was it strange to go back to the Netherlands? Vliek nods. ‘I still remember when I came back in 2014 for my Master’s programme; I was amazed by how little security there was here. Huge groups of people like those at Dutch festivals are unheard of in Kenya, because of security reasons. Every supermarket has a metal detector. In the Netherlands I think we enjoy a unique degree of freedom in this respect. At a festival, they mostly just check whether you’re trying to smuggle in alcohol. How great is that!’

She’s not trying to play down the attacks. A violent death is a terrible thing. ‘But I do think Mombasa has made me more pragmatic, and most of all that it’s given me the feeling that I shouldn’t let myself get frightened. There is absolutely no point in living in fear. When you do, you play straight into the extremists’ hands. That’s why I try to avoid thoughts such as “It could happen to me too”.’

Evil

We are passing Hotel New York, located in the former headquarters of the Holland-America Line, where once upon a time thousands of Europeans, full of hope for a better life, left for North America. Vliek is concerned about Trump’s election in the US and the wave of right-wing extremism in Europe. She finds fear of immigrants unnatural. ‘I think it’s an intrinsically human characteristic to want to get to know each other. We are social creatures. And especially with people who are really different, you can learn so much from each other. I think it’s a terrible thing that immigrants – and nowadays that usually means Muslims – are seen as something evil, something to be afraid of. Besides, this completely does away with the incredible diversity among people who use the Quran to guide their lives.’

‘We still live in a white man’s world’

But she also sees the other side of populism. The strong reaction it engenders. Ideals are sharpened; emancipation movements get a wake-up call. ‘You might argue that this shouldn’t be necessary, but I think that even before the rise of right-wing populism, Europe and the US had a long way to go with regard to emancipation of minorities. This has just become more visible now. As the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie points out: we still live in a white man’s world.’

The white metal wires of the Erasmus bridge tower over Vliek’s head. We’ve reached the end of our boating tour. Al Shabaab’s last big attack took place in April 2015, at the university in Garissa. 148 students died. Vliek attributes the relative calm that followed to the hard line taken by the Kenyan government. The police now immediately shoot down anyone suspected of terrorist activities. Kenyan Al Shabaab recruits are put on the spot by the home front: either they help dismantle Al Shabaab or, as The Economist formulated it earlier this year: ‘They can refuse, and risk being ‘disappeared’ by the police.’

Vliek and her Englishman still go back to Kenya on a regular basis. Whenever they are in Mombasa, they always remember to drop by to see Vliek’s former colleagues. But nobody talks about the attacks from the time when she worked there. ‘Once it’s no longer in the news, people don’t find it so important. Life goes on, I guess.’