Summer interview (4): The sky was the limit for Jordy Davelaar, until he got cancer

-

Jordy Davelaar. Photo: Duncan de Fey

Jordy Davelaar. Photo: Duncan de Fey

Astronomer Jordy Davelaar had just started his dream job in New York when he found out he had cancer. After a tough rehabilitation, he's now pulling himself back out of the depths and dreaming of returning to the 'city that never sleeps'.

What do you do when you’re told you have cancer but not which type? Jordy Davelaar (29) started googling like mad. “When I was finished, I had a list of the kinds of cancer I might have with corresponding chances of survival varying from 30 to 90 percent.”

Davelaar is an astrophysicist, a man of numbers and to a certain extent, he approaches his illness as a scientist. “When you become ill, it’s all about odds and expectations. I project them on myself. I’m well aware what my chances are – there are no guarantees. I look at that rationally.”

‘Cancer is a game of odds’

Naturally, the fact that he turned out to have a rare form of germ cell cancer can’t be called lucky. But given the circumstances, it wasn’t the worst case scenario, he explains as we sit at a pavement café on the Joris Ivensplein. “My kind of cancer can be treated relatively well with chemotherapy. Around 70% of the people who are diagnosed with this stage of this cancer is still alive after five years. The glass is more than half full. If I had been diagnosed with a wrong type, it might have been end of story.” Germ cell cancer in men is usually found in the testicles but Davelaar has a tumour in his chest.

Percentages are just percentages, as Davelaar knows only too well. There are no guarantees with cancer. “I was unlucky to get this disease at my age. There’s probably more chance of being run over by a bus. Now I just need to be lucky enough to survive it. My body has to respond the right way to the disease and the treatment and that’s a question of having the right genes. Cancer is a game of odds.”

While we’re still talking, an hour later, a motorist tries to turn into the Lange Hezelstraat. There’s a loud bang that resonates across the Joris Ivensplein. A bus has hit the car side-on. “See what I mean,” says Davelaar, “there’s a much greater chance of being hit by a bus.”

Unidentified mass

The first symptoms of Davelaar’s illness appeared in October last year. He had just moved to New York to work as a researcher at Columbia University and the prestigious Flatiron Institute – a dream job.

As a doctoral candidate in Nijmegen, Davelaar had shown himself to be a science talent. He became a member of the international Event Horizon Telescope team that made the headlines in 2019 with the very first photo of a black hole. Individually, the young astronomer attracted attention when he made a virtual reality simulation which allows a black hole to be viewed close up.

His accomplishments did not go unnoticed. Last year, Elsevier Weekblad magazine listed Davelaar as one of the thirty greatest talents in politics, science, culture, sports and industry. The expression ’the sky’s the limit’ seemed to be thought up especially for him.

After gaining his PhD in Nijmegen, Davelaar crossed the Atlantic Ocean. “I’ve been fascinated by America since I was a child. I knew New York already – I stayed there for six months during my doctorate. The enormity, the people, all those cultures coming together.” He used to enjoy walking into the city on his afternoons off, with no specific destination, often ending up on a bench with a cup of Starbucks coffee.

During that period, he was troubled by mysterious symptoms, which turned out to be a foreboding for the tribulations that awaited him. “A bad cold, swollen glands and retaining fluid in my neck. I thought the latter was probably due to swollen lymph glands from an infection, maybe a virus or the result of the flight.” The symptoms gradually disappeared. Davelaar threw himself into New York life, as far as that was possible during a pandemic.

But the symptoms came back in December, more severe than before. Davelaar was back in the Netherlands, to escape a long Covid winter in New York and to spend Christmas with his family. Back in Nijmegen, a friend distrusted matters: “This is not good,” she said. “Make an appointment with the GP.”

The family doctor was initially not too concerned. “Logical,” recalls Davelaar. “You’re looking at a young guy who never takes drugs and plays a lot of sports. Who’s going to think of cancer straight away?” After an echo of the neck, the doctor did become concerned. The mood changed. “Within three days I had to report to the CWZ hospital for a blood test, an x-ray and an interview with the internist. “‘We think it’s cancer,’ the GP said.

‘You know it’s bad, but how bad?’

The x-ray didn’t leave much room for optimism. The lungs are meant to go straight down normally, but Davelaar’s lungs were being pushed to the side. There was obviously something there that didn’t belong. A CT scan was made in all urgency and it revealed an unidentified mass. “They couldn’t say exactly what it was, but it was obviously bad,” says Davelaar.

He was admitted to the CWZ hospital. A biopsy (microscopic examination of tissue) was to indicate what kind of tumour was nestling in Davelaar’s body. The results took a long weekend to arrive. “That was the hardest of all. You know it’s bad, but how bad? What kind of cancer do I have? Can it be treated? What else is going on? My world was turned upside down.”

He finds it difficult to describe how he felt, lying there in hospital, alternating between hope and fear. “I think you have to have experienced it yourself. I was going mad there in hospital. Covid restrictions meant only one visitor a day. Every time a doctor came in, I thought: ‘now I’ll get the results’ but they kept needing more time.”

In the meantime, Davelaar was already able to read which kinds of cancer were being considered in his patient file. And that’s when he started searching the Internet, making lists with corresponding survival rates. “I had my own ranking: ‘I hope it’s this’ and ‘it absolutely must not be this’.”

Strong stuff

Now and then, Davelaar takes off his New York Yankees cap and runs his hand across his head. His hair is starting to grow back. He used to have quite long curly hair. Just before it was going to fall out, he took the electric clippers to it.

“People used to say I looked like Guus Meeuwis. After I had shaved my head, it turned out I resembled Philippe Geubels more.” Quite appropriate, says Davelaar about his likeness to the Flemish comedian. For Davelaar, humour is a way of dealing with life. My parents passed that mentality on to me. As long as you’re still able to make jokes, you’re all right.”

He feels that even if you have cancer, you shouldn’t take life too seriously. And that’s how he and his Brabander room mate in Radboudumc hospital wreaked havoc in the ward during Carnival. “Streamers, balloons… we had decorated the whole room. It was the talk of the hospital for days afterwards. Things like that help to make the situation more bearable.”

In the meantime, Davelaar was finding out the effect that chemotherapy can have. “After I was transferred to Radboud hospital, the doctors wanted to start the chemotherapy as soon as possible. They said it could make me feel better fast.” And that’s exactly what happened. He felt better after just two days. “That fluid retention in my face disappeared, I started to sleep better, my neck troubled me less. A nurse came to take a look after the weekend and said: “What on earth have you done? Strong stuff, eh?”

The treatment Davelaar was to go through consisted of four rounds of three weeks at a time. A round began with five nights in hospital where the chemotherapy was given intravenously. The rest of the week he was at home where his girlfriend looked after him. She is also an astronomer in the course of a PhD trajectory at Radboud University.

‘My life is starting to open up again’

“It was hard,” says Davelaar. “Your body is constantly destroying everything when in fact you only want to target the tumour. Your body is set on fire and that’s absolutely exhausting. I was sleeping for 12 hours a day, for weeks.” But ultimately, the treatment was not as bad as what Davelaar had prepared himself for. “The classic image of chemotherapy is constant vomiting. Thankfully, I didn’t have that.”

In the course of chemotherapy, Davelaar slowly recovered, mentally too. “It felt as if I were getting back control, that’s how it felt. By eating as well as possible, sleeping enough and getting enough exercise, you increase the chances of the treatment being successful. You hear the doctor expressing hope and as the patient, you start to live according to that hope.”

The moment he was waiting for was a new CT scan, in May. That would be the moment when he might get good news about the effectiveness of the chemotherapy. “I got really good news. My liver is clear. The large swelling in my chest has broken in two and shrunk. The doctors expect that my body will have to rid itself of that dead material and that will take time.”

Calmer waters

After the roller coaster of the last six months, Davelaar has now entered calmer waters. And that also takes some getting used to. “I research black holes and I fell into one myself.” The doctors hope that he will not need any new treatments but that’s not certain yet. A new scan isn’t scheduled until September.

“I work part-time, at least I try to. And I’m taking a lot of exercise: running, swimming, hiking. I’m trying to build up my fitness level again. I’ve been vaccinated against Covid and my life is starting to open up again.” He laughs. “My chemotherapy coincided with the lockdown, so luckily I didn’t miss that much.”

Davelaar is also aware of the stories about people who, having looked death in the eyes, turn their lives around radically by stopping work, for example, or working fewer hours. Davelaar hasn’t noticed this inclination in himself yet. “I didn’t work eighty hours a week anyway; I try not to get sucked into the madness of working overtime in science. I have a life outside it too.”

At the same time, the realisation of what has happened in the last months is only slowly dawning on him. “Because of the struggle, I haven’t really had the time to reflect on everything that’s happened to me. I haven’t given myself that time yet, also because I’m still in the process. There are a lot of green lights, but I’m not there yet.”

The hope is that Davelaar can return to New York in the autumn. “I dream of that. Literally.”

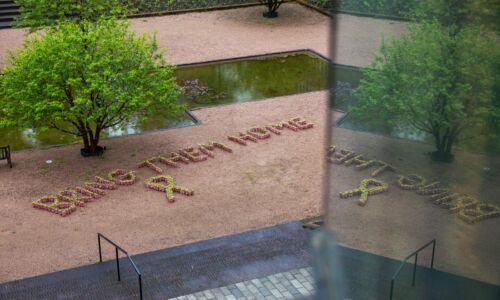

You Never Walk Alone

During his rehabilitation, Jordy Davelaar started a funding campaign with the title You Never Walk Alone to raise money for the Radboud Oncology Foundation. As we write, he has raised almost 4,000 euros. “I wanted to give something back,” he says by way of explaining his motivation. “It’s thanks to the doctors at Radboudumc hospital that I’m still here.” In return, Davelaar will do a 20-kilometre walk this summer, one kilometre for every night he spent in hospital. It’s not too late to donate.