Summer interview (5): Pastafarian Mienke de Wilde

-

Photos: Duncan de Fey

Photos: Duncan de Fey

For nine months now, Law student Mienke de Wilde (31) hasn’t been allowed to drive because she insists on wearing a colander on her head on her ID photograph. The municipality won’t allow it. She says: my religion prescribes it. What drives this obstinate Pastafarian?

She could also take it off, the colander. So that people on the street stop calling her names and the municipality agrees to extend her driver’s license, which they refuse to do as long as she wears one on her head on all her ID photographs.

But no matter how much inconvenience she experiences from her original headgear – most people use it to strain broccoli or pasta – Law student Mienke de Wilde refuses to take off her colander.

It’s all a question of principle, the right to be different, and spaghetti.

‘I’ve always felt that I didn’t really belong’

Where to start? Maybe in the mid-1990s, in Epe. Mienke de Wilde attends a primary school where children sit in class wearing only socks on their feet. The wooden clogs that betray their origins are neatly lined in the hall. Mienke herself does not come from a farm – she lives in a regular row house, with her two sisters, mum and dad. She wants to be a truck driver, because she often sees her father, who works in a workshop, at the wheel of one. Unfortunately for Mienke, the future has other things in store for her: she is too clever to limit her world to the cabin of a truck and trailer. She ends up in grammar school. She prefers to spend her free time outdoors, on her grand-father’s farm.

‘I’ve always felt that I didn’t really belong’, she explains. ‘On the one hand I was a real country girl, on the other hand at school I would lose myself in classical languages.’ Not a real country girl at all, really, although she does speak with an accent. This led to her also feeling uncomfortable among the ‘intellectuals’ at grammar school. ‘From a young age, I tried to figure out how group pressure works. For example, I found out early on that when people ask you: ‘How are you?’ they don’t really want an answer. They only ask because everyone else does; it’s one of those group things. I found it fascinating and strange. I wasn’t good at it – I didn’t understand the codes.’

‘I’ve always felt that I didn’t really belong’, she explains. ‘On the one hand I was a real country girl, on the other hand at school I would lose myself in classical languages.’ Not a real country girl at all, really, although she does speak with an accent. This led to her also feeling uncomfortable among the ‘intellectuals’ at grammar school. ‘From a young age, I tried to figure out how group pressure works. For example, I found out early on that when people ask you: ‘How are you?’ they don’t really want an answer. They only ask because everyone else does; it’s one of those group things. I found it fascinating and strange. I wasn’t good at it – I didn’t understand the codes.’

A few years later, when things get rough at home, this lack of understanding contributes to her breaking down. The insecure teenager becomes depressed and is hospitalized. She doesn’t really want to talk about this dark period, but her struggle with life lasted a few years. When she finally returns to secondary school, people try to convince her to switch to HAVO (professional secondary education). They reason that at least then she’ll have something. She does keep in touch with the classical languages teacher, though. ‘I would visit her to have tea. She played a really important role in my life. She saw that I had potential and told me that I was a worthwhile human being. She was always supportive.’

Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster

In 2005, the American Bobby Henderson founded the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. It’s a religion that primarily asks questions. Why would the world not have been created by a spaghetti monster? The Church has its own gospel and followers across the world, of which approximately ten thousand in the Netherlands. Discrimination is one of the themes the Church preaches against. In the Netherlands, a number of lawsuits have been brought against municipalities that refuse to approve a passport or driver’s license photograph with a colander. Radboud University Philosopher of Law Derk Venema frequently acts as advisor to Pastafarians. He denounces the fact that religions are not treated equally and raises the question of what makes a religion a religion. In a number of countries, including the US, colander suits have already been won, and in New Zealand the Church performed its first wedding ceremony last year.

Living at home was not an option, so Mienke moved out before her eighteenth birthday. On her own, after obtaining her HAVO diploma, she worked her way through adult education to an academic level, so that she could study at university.

‘I tried architecture and veterinary medicine. No classical languages unfortunately. I had a B-profile and I thought I should first try to do something with that.’ After moving around for a while, she ended up in Nijmegen. At the Law Faculty. Why? Out of idealism, primarily. Mienke de Wilde had turned into someone who takes things to heart. Who stands up for refugees (it’s not their fault their government is waging a war), fights against discrimination, and organises a bus for students to protest in The Hague against a world leader who excludes people (Trump’s Muslim Ban).

On the tractor

That thing about the bus, that’s later on, though, in late 2016. She first enrols at Radboud University in 2014 while living in Vorden, in the Achterhoek. Yes, in the countryside she loves so much. How wonderful after a day of lectures to jump on the tractor and join the men on the land. Her boyfriend, whom she meets on Internet, owns a contractor company there. He and his personnel fertilise soil, cut grass and chop corn for the local farmers. In the canteen, everybody speaks in dialect.

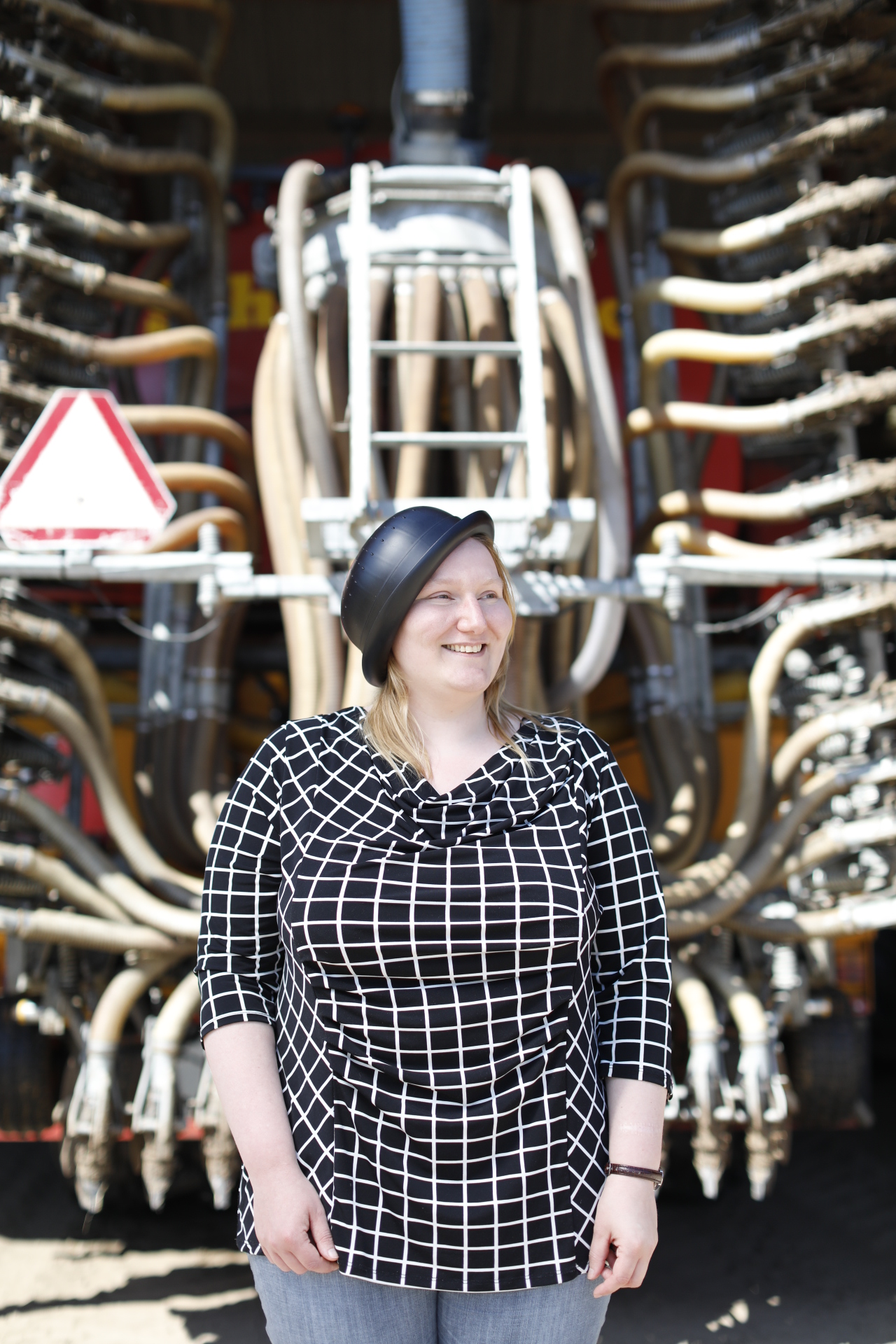

It’s here, on a beautiful June day under a perfect blue sky, that we hold our interview. ‘Now that I don’t have a driver’s license anymore, it’s not so convenient, living here’, she says while giving us a tour of the grounds. She looks like a dwarf against the background of massive agricultural machines.

O yes, her driver’s license. The one she stubbornly continues to fight law suits over. The more resistance she encounters, the more fundamentalist Mienke becomes. She wants the municipality to allow her to wear her ubiquitous colander on her ID photograph. The reason: it’s an expression of her religion, Pastafarianism. Mienke believes that the world was created by the Flying Spaghetti Monster. A year ago, she officially converted to this religion (see box). It’s not up to the municipality or the government to determine whether a religion is a real religion or a parody, she argues. She wears a colander on her head every day to express her devotion to the Flying Spaghetti Monster, just as Muslim women wear headscarves and Jews a skullcap.

The Flying Spaghetti Monster may well have saved her. It’s in any case the reason she still studies Law in Nijmegen. She’d become quite disillusioned by her second year. ‘My choice for law was strongly rooted in my sense of justice.’ Imagine her disappointment when she found the lectures were mostly concerned with rules at regulations. ‘At university I want to be able to ask questions like why? As if law books were some kind of Holy Scripture: this is what was written.’

Luckily she chose Philosophy of Law as a third-year subject, and there found space for asking questions. One of the seminars focused on a lawsuit against a Dutch Pastafarian. ‘Let’s attend the appeal hearing for fun’, Mienke suggested. And so they did.

‘It’s a very humorous religion’

Pastafarianism fascinated her. Here was something she wanted to belong to. Especially since you didn’t have to belong to belong. ‘The thing that connects us is that we are allowed to be different.’ Which is perfectly in line with her aversion to uniformism. People nowadays are quick to kick out of the nest anyone who is different. Intolerance has become the norm, notes Mienke. ‘Not only Muslims, but anyone with a different view is a target.’

And there’s something else. She sees wearing a flashy colander in public spaces – at the Gamma, the village baker, the cinema – as training in not taking criticism personally. This was not her original intention, but it certainly works. As someone who’s always been sensitive to other people’s opinions, she now catches herself thinking ‘whatever!’ ‘You have to ask yourself what you really find important: other people’s opinions or what you think. Philip Zimbardo (of the Stanford Prison Experiment, eds.) says that if you want to practise resisting group pressure, you should walk around for a day with a black dot on your forehead. And not care what people say.’

The colander is her black dot. This gives the object, which can be purchased at any ailing Blokker store, a therapeutic value. The symbolism is also interesting: spaghetti strings stand for chaos and by walking around with a colander on your head, you learn to separate the essential from the frivolous. The Flying Spaghetti Monster is not an almighty deity as in other religions – a kind of perfect human – but a monster made of spaghetti and meatballs who created humanity in a drunken moment. He would never look down on ordinary mortals.

‘It’s a very humorous religion’, admits Mienke de Wilde. ‘And the humour is precisely what helps you put things into perspective. Religions that take themselves too seriously may run into conflicts; examples abound all over the world. We don’t have Ten Commandments, but eight ‘rather nots’. One of them boils down to this: respect other people’s opinions and beliefs.’

‘Maybe people are just more used to strange things in the Achterhoek’

Funnily enough here in the Achterhoek people are much less quick to comment on her colander than in highly educated Nijmegen. ‘I didn’t expect that. The first time I went to the supermarket here I was really scared. But maybe they’re just more used to strange things here, with bands such as Normaal and Jovink – who are always getting up to funny stuff.’ In Nijmegen someone called out to her the other day that she stank of spaghetti – and not just anyone but a young father holding a small child by the hand.

Incidentally she didn’t run into any problems at the University, she hastens to add. She keeps her headgear on during lectures and examinations, and attends the most serious meetings of the Law Programme Committee ‘as herself’. For a while now, she’s been working as a student assistant, with her colander on. In future she hopes to do a PhD.

As a professional researcher she plans to continue to live in the countryside; it’s good for her. The peace, the space… and of course love. Two months ago her boyfriend proposed to her. In his own way. With a cultivator he wrote three words in a field, followed by a question mark: ‘Mienke marry me?’

The fact that she might appear at the altar wearing a colander on her head is a non-issue. He loves her and will continue to do so, even if she starts wearing an orange mixing bowl.

Change wanted schreef op 9 augustus 2017 om 11:38

This article is overshadowed by the use stereotypes by a biased writer of which I want to highlight two. I would urge Vox and/or the writer to make changes to the article as to be more respectful against those offended by these generalisations. Judge yourself:

First fragment:

” On the one hand I was a real country girl, on the other hand at school I would lose myself in classical languages.’ Not a real country girl at all, really, although she does speak with an accent. ”

Stereotype: Girls from the country side cannot have an interest in classical languages.

Second fragment:

“She wants to be a truck driver, because she often sees her father, who works in a workshop, at the wheel of one. Unfortunately for Mienke, the future has other things in store for her: she is too clever to limit her world to the cabin of a truck and trailer.”

Stereotype: Truckers are not as clever as people who go to university.

Change not wanted schreef op 9 augustus 2017 om 17:40

The first “stereotype” is a personal statement and a good reflection of this persons big interest in herself and the need to show off her uniqueness as a person

The second “stereotype” is an unideal use of words since the writer is confusing the words “clever” and “intelligent”, the assumption that people that go to university are more intelligent than the people who drive trucks is just accurate in the case where they get a fair chance at the education system like this annoying girl clearly did.