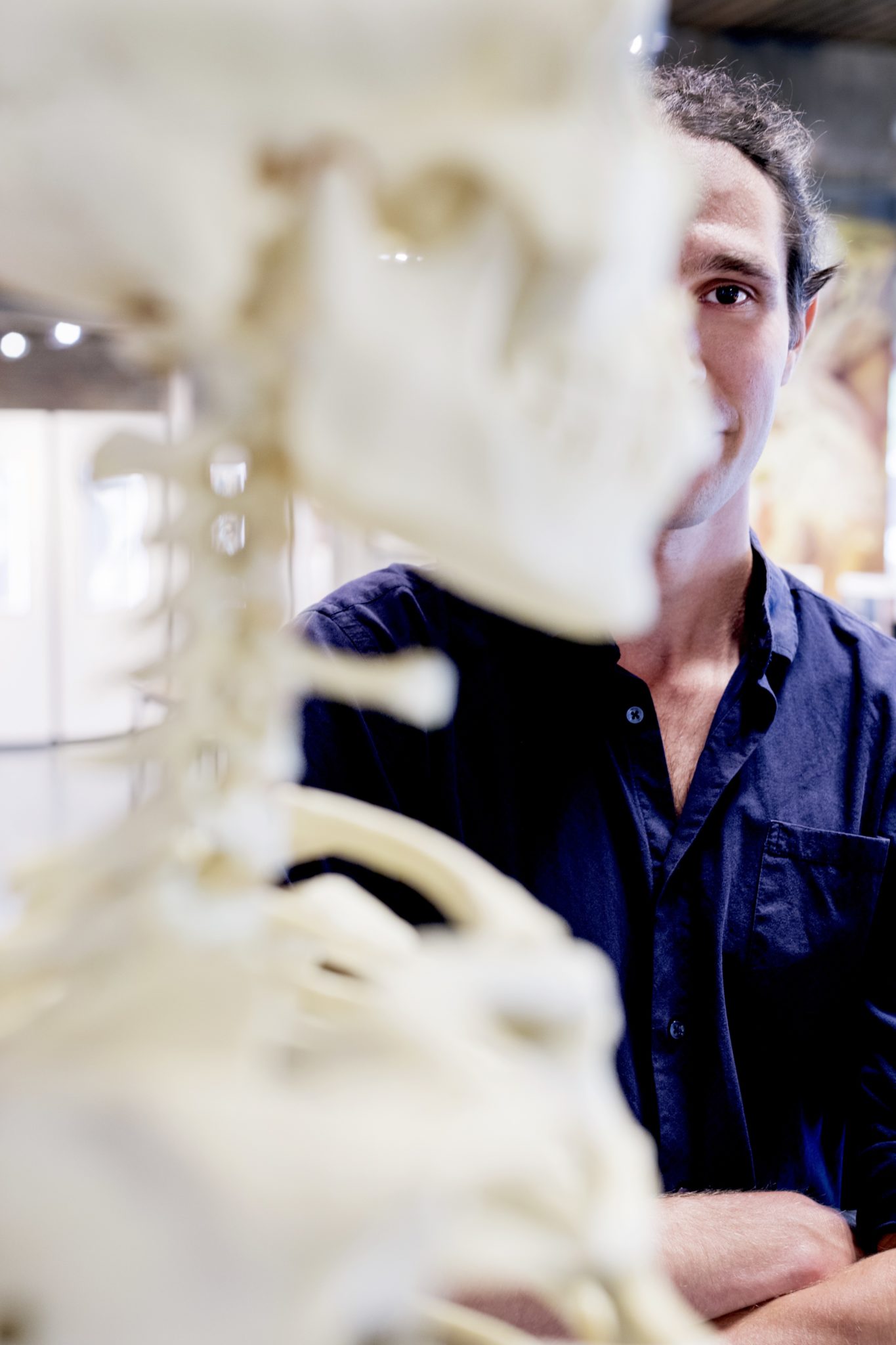

Summer interview (7): Lucas Boer

Lucas Boer (30) was once told to become a carpenter or an electrician. He’s now curator at the Museum of Anatomy and Pathology, and is working on his PhD. People haven’t always understood his fascination for dead things.

‘Even at primary school I used to love to sit in the bushes and dissect dead birds. I would look at how they were put together. We once went on an excursion to the petting zoo, and the teachers discovered I’d brought a pocket knife with me. It was a huge drama – my parents were called in, the works. But I’d simply brought that pocket knife along because I thought I might find owl pellets to dissect. I ran into a lot of resistance to my interest in dead things. Of course, it’s easier to understand your child being crazy about football. Apparently I didn’t fit in the neat categories and so they advised me to attend a ‘vocational college’, to become a carpenter or an electrician. My mother didn’t allow this to happen, luckily, so I went to the MAVO school in Oss instead.’

‘I must have been about thirteen years old when I brought a dead cat home in my backpack’

‘I must have been about thirteen years old when I brought a dead cat home in my backpack. I’d found it in a meadow, and it was still fresh. My parents weren’t particularly pleased about this, but I was raised with lots of freedom, so they didn’t stop me. I dissected the cat and boiled it. It works just like with a chicken: if you boil it for long enough, it falls apart all by itself. You’re left with a puzzle of loose bones. This is how I taught myself to skeletonise, even though I had no clue at the time that this was the way to clean a skeleton perfectly. Now I’ve skeletonised more than one hundred animals: birds, lions, seals, and many more. They usually come from zoos or private individuals, and in most cases I return them to their owners in skeletonised form. A natural posture is very important: it has to look as if they simply ran away. What I’m interested in is creating something out of a dead animal that will fascinate the viewer. Only then will people be willing to look at it, which can lead them to new insights.’

When you think about it, I’m still doing the same thing, but now with people. After the MAVO, I went on to secondary laboratory education, which most closely matched my interest in biology and nature. Then I completed my higher laboratory education. In my final year I wrote a letter to the Radboudumc Museum of Anatomy and Pathology: ‘Can I work for you?’ I sent in photographs of my skeletons and was immediately hired as a taxidermist.

On my first day, I was invited to sit in on a course to teach medical students how to make preparations from bodies. ‘This will be your first experience of cutting a human body,’ said the curator. For me, there was little difference. I saw it as just another body, not a human body. In my mind, I’d immediately made it into an object. A body was a person once, but that person’s spirit is no longer there. I really see it as separate from a living person with their unique personality and experiences. I have to. Otherwise I couldn’t do this kind of work. For that course, I had to make a preparation of a woman’s inguinal canal. I won the prize for the ‘most attractive preparation’.’

Tiny scissors

‘The Anatomy Museum serves an educational purpose. Students come here to study how the human body is structured, and where things can go wrong. We also teach dissection courses, using bodies that were donated to science. Every year, the anatomy department receives one hundred bodies or so. I only prepare body parts to be exhibited in the museum, to add to our collection.’

‘We never make anything just for fun, only if there is an educational need for it. But we do display our preparations in a way that makes them interesting for regular museum visitors. I’m never completely satisfied with a preparation. A beautiful preparation is much harder to make than a beautiful skeleton. One arm takes up to three months to complete. You have to remove every single membrane, because any debris will end up swimming in the formalin, which distracts from the preparation. Any loose edge makes it look gross. We use tiny scissors and knives to get it to look perfect.’

‘Some children are four hundred years old’

‘I’m always looking for a challenge. Three years ago I was appointed Curator of the Museum, and next year I hope to complete my PhD. It’s difficult as a non-academic. Someone has to be willing to give you a break. I was lucky that Professor Dirk Ruiter saw my potential and gave me this opportunity at Radboudumc. Dirk is now my thesis supervisor.’

‘For my research, I’m mapping the Dutch teratological collections. The Greek word τέρας (teras) means wonder or monster, it has a double but also a negative connotation. It’s used to refer to children with congenital disorders. They’re preserved in formaldehyde at various anatomy museums. The odd thing is that remarkably few people do anything with them. These children were collected a long time ago because some physician found them so unique he wanted to keep them. Often they’re no more than a kind of rarities cabinet. People look at them with horror, or snicker about them uneasily. I saw these kinds of reactions in our museum too, and I felt terrible about it.’

‘Our collection consists of 72 children, collected between 1950 and 1980. You have to understand that these were completely different times: these children were born dead or died immediately after birth and were usually quickly taken away from their mothers. There was a taboo about it. It’s not even clear whether all the parents gave permission for them to be used in the museum – nowadays this wouldn’t be possible. And yet, we decided to exhibit the children. Such severely malformed babies are rarely born these days, thanks to our much-improved prenatal screening techniques. The medical value of this kind of collection is priceless. Only in these old collections can you see what a congenital disorder actually looks like, especially at an advanced stage.’

‘When the museum celebrated its 50th anniversary in October, we organised an exhibition around this collection. We picked out the 35 most interesting preparations and placed them in new containers, replacing the old formalin. For most of these children, we don’t even know their name, or what year they were born in. By displaying them in an attractive way, I hope to give them back some dignity. All the preparations were supplied with information, to make it less scary for visitors. I invite medical students and young physicians to look at the children in the museum and name what they see. What diagnosis would they make? Then I show them MRI scans. These often reveal much more still.’

Siamese twins

‘For my PhD research I’m trying to map as many children as possible from the Dutch teratological collections. Unfortunately, we can’t scan all the preparations, because some museums are very attached to the original containers and labels. In such cases, you can’t say: ‘I’ll just take the preparation out for a minute.’ Some are four hundred years old. What I hope is that with thorough research, including the study of new scans, we’ll be able to identify patterns. That we’ll discover where a disorder originates. For this you really have to go back to the embryo phase.’

‘We’re currently studying Siamese twins. There’s a theory about their origin that is simply repeated from generation to generation. I happen to have a different theory, and I’m trying to articulate my vision by involving experts from other fields, like experimental development biology. Launching new ideas, asking questions, that’s what it’s all about. And then hoping for new insights.’

‘I recently heard someone use the word ‘morbid’ in reference to my research. For me it’s not like that at all. Anatomy is relatively simple: there are differences between people, but most bodies are built in the same way. Congenital disorders are elusive, and I’m fascinated by the complexity of the issues. How is such and such possible? My girlfriend is a doctor, and over dinner at night we discuss what we’ve seen that day. She wants to become a clinical geneticist, so we’re basically in the same field.’

‘I’m not afraid of death, but my work has helped me become aware that my life could be over any moment. A person dies, and 24 hours later their body is lying in the anatomy department. I think of death as the end. The flame goes out, and that’s it. Sometimes I’m alone in the dissecting room, surrounded by bodies – some of them quite recently deceased. If there was something beyond death, I’d have noticed by now, don’t you think?’