The occupation of the Erasmus building is part of a long history of student protests in Nijmegen

-

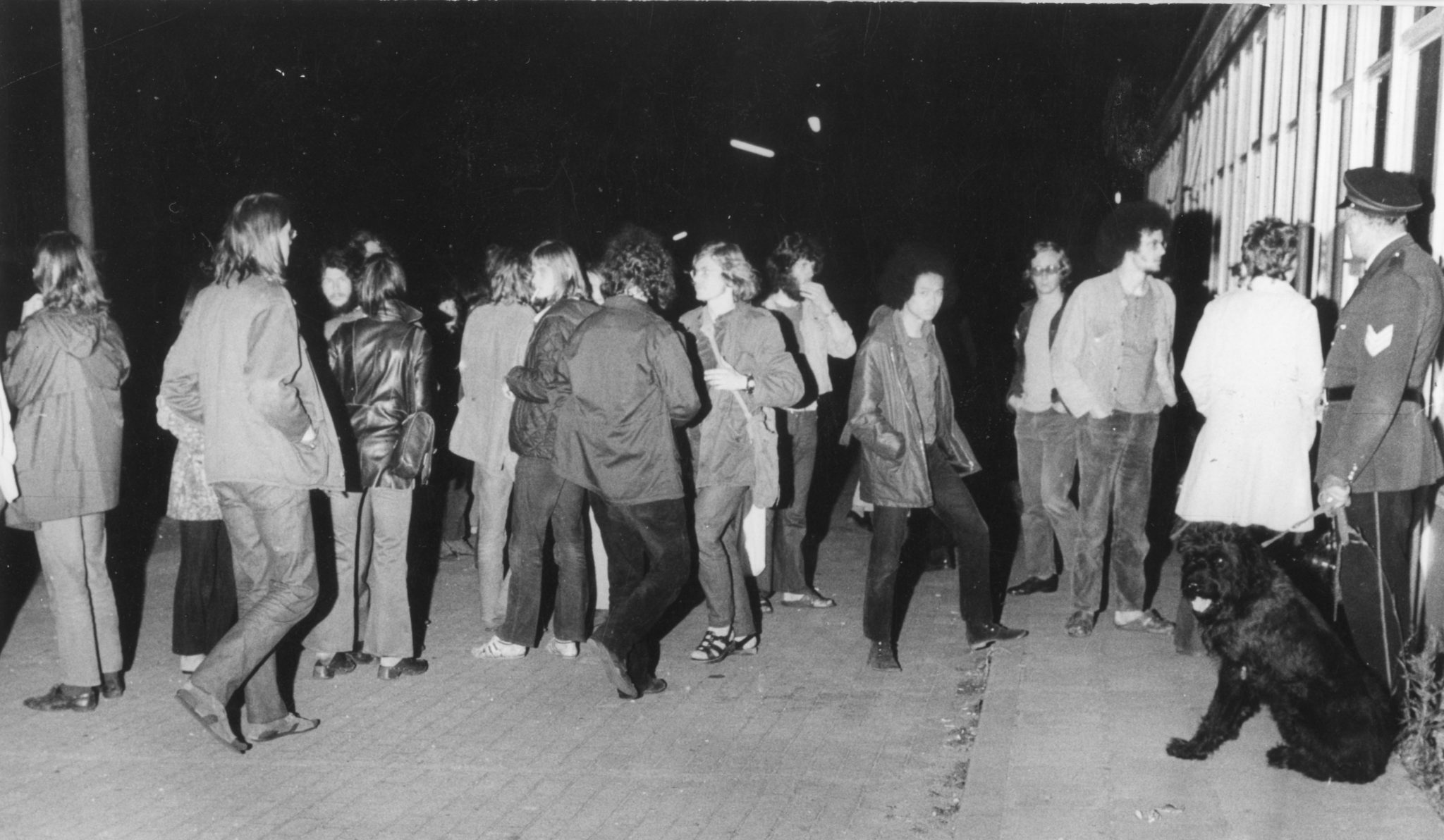

Protesterende studenten in 1977. Foto: Katholiek Documentatie Centum, Nijmegen.

Protesterende studenten in 1977. Foto: Katholiek Documentatie Centum, Nijmegen.

Last Monday night, the university briefly returned to the 1970s with the occupation of the Erasmus building and the subsequent evacuation of the building by police and the mobile unit. ‘The Erasmus building has had only one entrance for a long time. That’s why it was very attractive to occupy.’

Policemen making their way down the stairwell of the Erasmus building armoured with a shield and baton, a group of masked students waiting for them arm in arm, barricades being dismantled, and activists being taken away by the mobile unit: the images of the evacuation of the Erasmus building last Monday will live on in the collective memory of everyone associated with Radboud University.

By occupying the Erasmus building, students place themselves in a long tradition of student protests in Nijmegen. Especially in the 1970s, students often barricaded the doors of university buildings. ‘Back then, there were occasionally around ten occupations in a row,’ says Jan Brabers, the university historian, in his office in the very same Erasmus building. ‘On the other hand, I cannot remember an occupation or eviction of this magnitude in the last thirty years.’

First occupation

Nijmegen students occupied the auditorium of the then Catholic University Nijmegen on the Wilheminasingel for one entire day in the autumn of 1968. ‘In left-wing students’ analyses, university studies had become an instrument of capitalist society, whereas they wanted to study for the benefit of the people,’ says Brabers. ‘Through negotiation, talks, and consultations, the students tried to weaken government reports on the administrative redesign of universities. When they felt this was not going fast enough and threatened to even fail, they took to the barricades.’

Around 700 students occupied the auditorium. The protest went down in history as the very first student occupation of a university building in the Netherlands. ‘Lectures were abruptly interrupted or cancelled,’ says Barbers. ‘That made a huge impression. In the evening, students returned home, and police did not get involved.’

Six months later, students occupied the auditorium again. They had renamed the building the Permanent Discussion Centre on a large banner they hung on the façade. For ten days, they spent the night in the former administration building, at the same time as the famous occupation of the Magdalene House in Amsterdam.

Some meetings in the discussion centre had 1500 students present, about 10 percent of the total number of students at the time. ‘The occupation was very peaceful; students debated amongst themselves and with representatives of the university administration. That was democratisation in practice.’

Barricading doors

However, the glory days of student occupations were the 1970s. At one point, there were so many occupations that former Rector Magnificus Frans Duynstee threatened to call the police on the protestors. ‘That even happened a few times. It led to resentment, because students felt, as they do now, that the police did not belong at the university. As a reason, they referred to the old legal principle that a rector has disciplinary authority and decides what happens on campus.’

‘During the squatter riots, there were sometimes real battles with the police’

Those evictions, as Brabers points out, were often less peaceful than last Monday night. ‘Although it pales in comparison to, say, the squatters’ riots in the early 1980s. there were sometimes real battles with the police. Those riots did not take place at the university, though, but in the city, although students were of course also involved.’

Crucifixes

The Erasmus building, which opened its doors in 1974, has also hosted protesting students before. In fact, it was a popular location among activists. The building was already occupied on its opening day. Drinks, snacks, and a music band were waiting inside, while the state secretary of Education and Science Ger Klein (PvdA) and his entourage, which included the Executive Board, stood outside before a closed door.

For a long time, the Erasmus building had only one entrance. ‘If you barricaded that one, you had it all to yourself,’ according to Brabers. ‘That’s much harder these days.’ The many windows have also made the building suitable for student protests. ‘Students used them as an advertising pillar on which to stick their demands and slogans.’

Whereas the occupations in the 1970s began rather peacefully, over time there were also acts of vandalism. These lost the protesters some support. ‘After a while, things went missing or crucifixes were pulled from the walls,’ says Brabers. ‘That caused more resentment towards the occupying students. Locks were put on the room doors in the Erasmus building.’

After the 1970s, student occupations gradually faded. With the installation of a participation council, faculty councils, and regular elections, many student demands had been met. Even after that, there were a few occupations at Nijmegen University, but they never managed to reach the masses.

Key difference

Incidentally, the recent occupation of the Erasmus building not only had similarities with earlier students protests; Brabers also sees an important difference. ‘In the 1970s, the occupations of university buildings were about the essence of the university, about the demand for participation, which the students got in the end. Around 1970, students brought the outside world to the university, because even at the currently democratised university, poverty and Third World issues had to be discussed.’

Today, according to the university historian, students are protesting something less clearly related to the essence of the university. ‘That is also the reason they do not manage to reach the large numbers of students of previous occupations,’ he says. ‘The protest is not about the university, but it is something from outside. Of course everyone finds the events in Gaza disheartening, but the relationship with the university is still a bit dubious. I am aware that that is not the case according to the protesting students and staff, but as a historian I still think it is an important difference from previous occupations.’

Translated by Lieke Stevens