The ten plagues of a Nijmegen super telescope

-

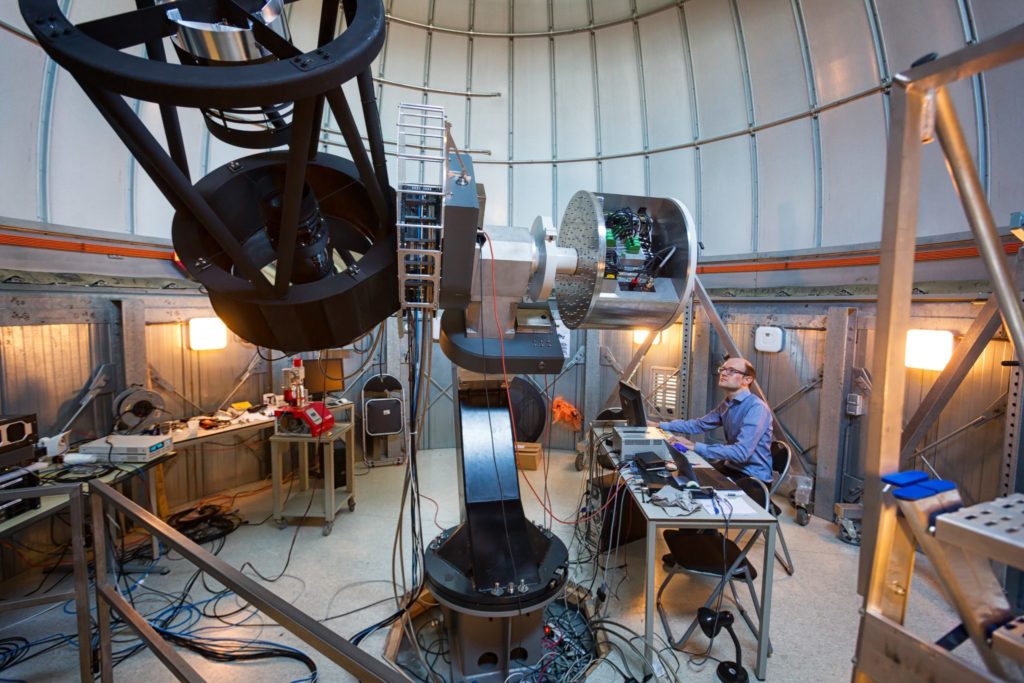

MeerLICHT's installation in South Africa. Photo: Twan Bekkers

MeerLICHT's installation in South Africa. Photo: Twan Bekkers

The most advanced optical telescope ever to have been built in the Netherlands was constructed in Nijmegen. After this summer, it will start observing from South Africa. Its journey was far from easy, says initiator Paul Groot. ‘We gradually found out why it is that no one ever tried this before.’ A reconstruction.

Paul Groot had an idea. An idea that was supposed to end the crux that astronomers prefer not to speak of: their observations are rarely ever on time. Whenever something peculiar happens in the universe, such as a star suddenly becoming much brighter, a slight panic ensues. ‘Oh dear, a star is exploding. Quickly! We must aim an X-ray telescope towards it, and a radio telescope, and, and…’ Various follow-up actions take place. By the time everything is running, at least 15 minutes have passed, and a lot has happened that the astronomers would have preferred to have on record.

And all this still happens despite the size and technology of telescopes becoming increasingly impressive. On the southern hemisphere, in South Africa and Australia, the world’s largest radio telescope is currently being built. This telescope will consist of several hundred dishes and will have a much better capacity to capture radio waves from the universe than all its predecessors; waves originating from evolving stars, or perhaps even from civilizations on other planets.

Eyes

How wonderful would it be, Groot thought to himself, if another kind of telescope would look into the universe at the same time as this mega radio telescope? An optical telescope that doesn’t catch radio waves but light, and that takes a picture of the part of the sky toward which the radio telescope is oriented once every minute. Two different eyes, which will see so much more when a star explodes. A superb idea, his colleagues thought. But they also thought: why haven’t we done this before?

Nearly five years have passed since that idea popped up, and Groot now knows why. The telescope has been realised. It’s called MeerLICHT (‘MoreLIGHT’) and is ready to be commissioned in South Africa. It is the most advanced optical telescope ever built in the Netherlands. A sizeable achievement, colleague astronomers said recently during a meeting at the European Southern Observatory headquarters in Munich when Groot showed the first images produced using MeerLICHT. But it was far from easy, he says, now back at his desk in the Huygensbuilding. As the pharaoh in ancient Egypt, he faced one plague after the other. A reconstruction.

Plague 1: Amazon.com fails

From the first moment on, Paul Groot’s plan was to simply buy his telescope. Look it up in a catalogue and order it online. It would still take six months to deliver, but even that would be faster than building your own. ‘The reason we did not buy it, is that we realised our requirements were so high that not a single commercial telescope was able to meet them.’

The telescope should take large photos, with high precision, as that will yield more information about the reactions in the universe. But the manufacturers proved unable to supply telescopes with such cameras. ‘We did ask them to produce a telescope with a larger field of view, but their answer was that it would decrease the image quality due to distortions.’ The only option left was to design and build a telescope themselves. Knowing that it would take much longer.

Plague 2: Teeny-weeny Netherlands

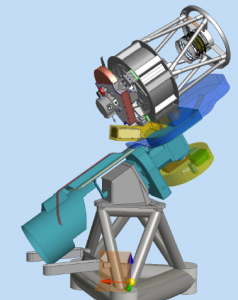

If you thought a telescope can quickly and easily be assembled: you are wrong. It all starts with the fact that the Netherlands does not have a single company that could provide all the parts necessary. The Dutch market is simply too small for that. The parts for the machine had to come from near and far. Marc Klein Wolt, Director of Radboud RadioLab, has spent considerable time networking with manufacturers around the world and assessing tenders. Eventually, the mirrors for the telescope were produced in the east of the United States, while the camera was made on the other side of the country, in California. A company in Hungary worked arduously on a mount with built-in motors, upon which the telescope will rotate.

Plague 3: Lack of money

It then became clear that the telescope would be much more expensive than budgeted for. Well over one million euros, including design costs. Groot expected a financial deficit of several hundred thousand euros. And he had all but given up. Colleagues were asking whether he hadn’t bitten off more than he could chew.

Paul Groot decided to reject other tasks to have more time to spend on MeerLICHT. He passed on his position as Department Chair to a fellow professor. As project manager, Steven Bloemen was the daily manager for the construction of MeerLICHT. Bloemen could not believe his luck: he had already worked on the construction of a telescope as a PhD candidate in Leuven, but he had never built one from scratch.

To Groot’s relief, additional funds were made available, thanks in part to the discovery of gravitational waves. The euphoria around the phenomenon that was predicted by Einstein but never before observed contains very high expectations from astronomical research. According to Groot, it seemed like the discovery had suddenly awakened everyone. ‘We have to do something!’ was the general feeling. That was the moment for Groot to raise his hand: we have already been working for three years! With our instrument, we will be able to see the sources of these gravitational waves much better. And it worked: Radboud University and the Netherlands Research School For Astronomy (NOVA) decided to invest much more. About 250,000 euros each.

Plague 4: Snowflakes

February 2017. MeerLICHT was transported to the Nijmegen campus from Dwingeloo, where engineers of research school NOVA had assembled the telescope. A crane carefully lifted the telescope onto the roof of the Huygensbuilding. Staff at the TechnoCenter of the Science faculty and volunteers from the Astronomische Kring Nijmegen (Astronomical Circle Nijmegen) made sure everything went smoothly. However, once the weather cleared up and the telescope could be tested, the astronomers saw large, blurry circles floating above the picture. What was going on?

Plague 5: Salt

Fast forward one month. Project manager Steven Bloemen stood amidst large wooden crates. These were made for MeerLICHT’s journey to South Africa. They were to be filled with feathers and foam, as the lenses and mirrors of the telescope are particularly vulnerable. The problem with the snowflakes had since been solved. It was caused by the fixation of the mount upon which the telescope rotates. It caused the telescope to wobble too much. The Hungarian manufacturer visited for several days, and the mount is now properly fixed.

The initial plan to transport everything by ship has been scrapped. Bloemen and Groot feared complications at sea. Salt could reach places where it could damage the material. And so, transport by air was the way to go.

Plague 6: Disappearing staff

Communication with South Africa was primarily via the local project coordinator. He was supposed to make sure that MeerLICHT would receive a warm welcome. Right? Bloemen was told that his South-African colleague had found another job. There wasn’t going to be any replacement soon. Communication and contact suddenly fell through.

Plague 7: Customs

And so they stood, with all their preparations and eighteen crates of parts, at the Cape Town airport. The date was 8 July 2017. Steven Bloemen explained as much as he could. But the customs officers were scarcely interested in the people on a mountain four hundred kilometres away who were itching to assemble the telescope – and who were idling while waiting. One day passed, two days – three days, even. The crane had already been ordered; transport was arranged. This could go wrong in so many ways.

Plague 8: Misplaced letters

It was as if an invisible hand had given wings to the technicians who worked with Bloemen and Groot at the dome in Sutherland, in the African highlands. MeerLICHT was released by the customs and had arrived! A group connected the parts, another was preparing the dome. In one night, everything had been prepared for the arrival of the crane the next morning. MeerLICHT had finally come home.

But frustrations arose when the astronomers realised the telescope was not rotating properly. Weeks later, it turned out to be a trivial programming error: two letters had been misplaced.

Plague 9: Defective chip

And then it was the camera’s turn. It had a defective chip, which could not be repaired. The Californian manufacturer produced a new one in record time. What normally takes a year was now done in a mere month.

Plague 10: Wrong screws

When Bloemen and his colleagues wanted to mount the new camera on the telescope, they discovered it was not possible. It had to be done with US imperial-sized screws. Attaching the camera with screws used in the rest of the world was simply impossible. But where are you going to find American sizes in the South-African highlands, four hundred kilometres away from civilization?

What next

It was worth all the frustration and setback, Paul Groot says in March 2018. Not just the size of the images produced by MeerLICHT is impressive, their precision is striking too: the images are sharp and focused even in the corners. The control room is on campus in Nijmegen, which means MeerLICHT is operated from Nijmegen. After the summer, it will be connected to the large radio telescope (MeerKAT) in South Africa, the most sensitive of its kind on the southern hemisphere. At that point, the double observation can finally start.

The telescope is already being used as a model for three more identical telescopes that will be placed in Chile. Steven Bloemen will coordinate their assembly as well. At the TechnoCenter of the Science faculty, the final touches are put on the design of the towers that will support the telescopes. The centre is also working on parts for the three telescopes. Meanwhile, Groot is discussing with astronomers in New Zealand. Similar telescopes are planned for that region as well. If it were up to Groot, MeerLICHT’s siblings would arise around the entire southern hemisphere. In the meantime, an official request to open MeerLICHT has reached the desk of the South-African Minister of Science.