This doctor lives a year at the South Pole

-

Foto's: Floris van den Berg

Foto's: Floris van den Berg

There is a place on Earth where for four months of the year the sun never rises and the temperature can drop to minus 80 degrees Celsius. It is here, on Antarctica, that Nijmegen GP Floris van den Berg has spent the past year.

Rather read this story in Dutch?

For a week now Floris van den Berg has had a pet, a caterpillar that made its way to the Pole Station Concordia hidden in a lettuce. ‘The caterpillar is the first living animal I’ve seen in a year. I call him Bertrand, after the cook who found him.’ The caterpillar now keeps Van den Berg company in his room. Every day the GP and researcher feeds him a lettuce leaf.

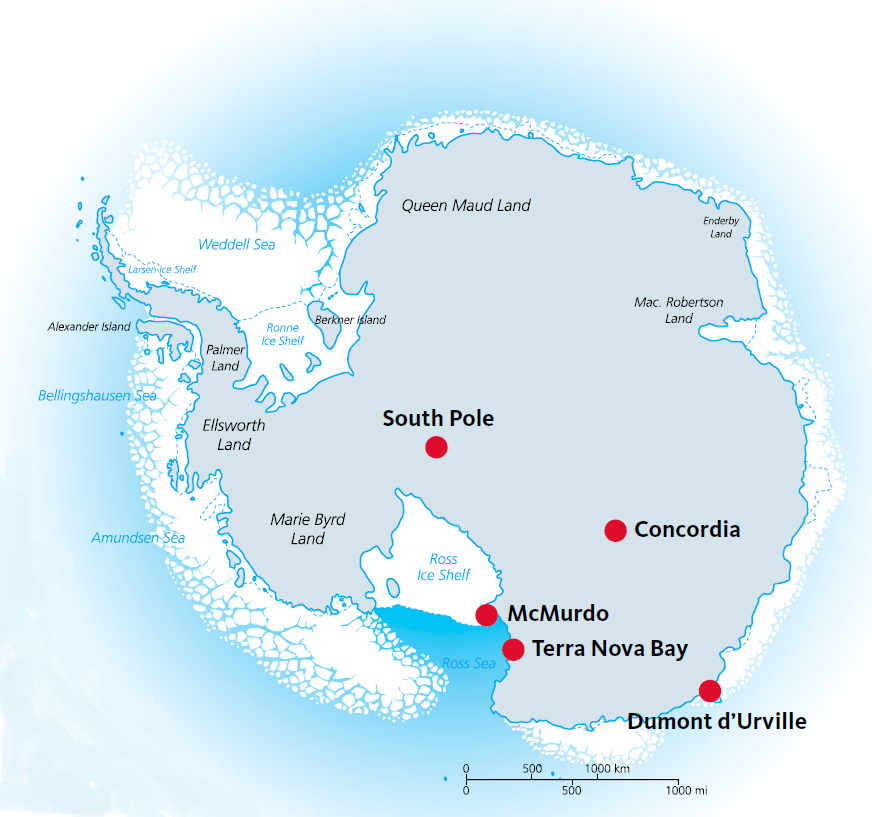

Van den Berg has managed to endure life at the South Pole for a year now – at the time of our Skype interview he still has seven weeks to go. With his webcam he gives me a glimpse of the South Pole: an empty white landscape stretching all the way to the horizon. Concordia is located about 1200 kilometres from the sea, so there are no penguins or polar bears here. All you can see is snow and blue sky.

‘It’s minus thirty today – a warm day. It’s summer now. In the winter the temperature sometimes drops to minus eighty.’ And when it’s windy, the wind chill makes it even colder still, says Van den Berg. ‘Sometimes it drops to below minus one hundred degrees.’

These are not temperatures for a nice walk outside. Just going outside is not an option, if only because of how long it takes to don three thick coats, a hat, ski goggles, and gloves. ‘Anything under minus fifty is no fun. You immediately notice if your goggles aren’t on right, or if your shawl doesn’t cover your face properly. After a few minutes your hands start to hurt. And within ten minutes your goggles freeze – I usually take a second pair along. There’s no way you can last longer than twenty minutes anyway.’

Antarctica is the coldest continent on Earth and is situated around the geographical South Pole. The terms South Pole and Antarctica are often used interchangeably. The continent is larger than Europe and almost completely covered in ice.

Antarctica is the coldest continent on Earth and is situated around the geographical South Pole. The terms South Pole and Antarctica are often used interchangeably. The continent is larger than Europe and almost completely covered in ice.

Pole station Concordia was opened in 2005 for French and Italian research programmes. Every year the space agency ESA sends one researcher to Concordia.

Mars

The European Space Agency ESA sent Van den Berg to Antarctica for a year to conduct research on the impact of extreme cold, thin air, and isolation on the people living there. Conditions there are somewhat similar to those on Mars, the planet where the space industry is so keen to send people. Van den Berg is staying on Concordia with six Frenchmen and five Italians, all of whom are doing scientific research or maintenance work at the Concordia station. One of them is a cook. Only Van den Berg is here on behalf of the ESA.

One of the things he is studying is the effect of extreme isolation on the brain and the heart. The future crew of a voyage to Mars will have hardly anything to do for months on end, yet must remain sharp in case life and death decisions have to be made. Is the human brain still capable of carefully landing a spacecraft on the Red Planet after months of boredom? It is hoped that tests in a simulator and the work of the Nijmegen GP will provide answers to these kinds of questions.

What did you discover during the course of your research?

‘From a scientific perspective there’s not much I can say about it yet. Every month I collect blood and urine samples from my eleven co-residents and myself. I also measure our bone density at intervals using a CT scanner. All these data are collected and sent to universities to be studied and interpreted. All the inhabitants of Concordia also wear special smartwatches that keep track of all kinds of data on their sleep patterns, heart rhythm and where they are located within the station. This data shows me that people tend to withdraw more in the winter. Of course, I’ve also seen with my own eyes how people who live here for an entire year behave. Winter is the hardest season, when the sun doesn’t rise. Not everyone copes with this well.’

What’s it like to live without sunlight for four months?

‘I personally didn’t suffer from it too much, but it’s hard. The dark months seem to last forever. People withdraw; they no longer want to take part in joint activities. Everyone becomes sluggish: I often had the feeling that I was living with eleven zombies. As a GP I know the criteria for depression, and some people certainly fulfilled them. The funny thing is that you don’t actually sleep as well when it’s dark all day. You might sleep as long as before, but your energy level still drops. When the sun finally reappeared, it was as if we had all woken up from a long hibernation.’

How did you keep your spirits up?

‘You have to keep motivating yourself. The team provides little support. We all have our own work to do. I managed by checking things off in my diary. I would think of everything I wanted to do in the coming week. If I completed a task I would give it a green tick, if I didn’t complete it a red cross. It’s really childish, but it worked. I just did my work and every day I exercised for an hour. Some people didn’t manage to keep this up – they spent more and more time in bed.’

Is it still fun to be with your colleagues?

‘We eat together every day. When it’s somebody’s birthday we drink a glass of champagne. But we spent less time together as time went on. After dinner everybody just disappeared into their own room. There was often a lot of tension and conflict. About the silliest of things. Someone would complain every day about being cold, even though the inside temperature is regulated and the same every day. Some people thought people should not be allowed to eat more than one yoghurt per day. Others thought they should not have to clean. Those kinds of squabbles.’

Doesn’t sound like fun.

‘Well, you can hardly blame people. Some of them are simply unhappy and not suitable to be here. It’s their employers who are to blame. Especially the Italians, half of that group were not properly screened beforehand. The Italian institute that does research here primarily looked at their CV. But you have to have a certain kind of personality to endure here. In the beginning we tried to function as a single group, but after a while the team split into two smaller groups.’

Globetrotter Floris van den Berg (33) is GP and expedition doctor. He studied Medicine in Nijmegen from 2001 to 2009. During that time he took photographs for ANS. When he is not travelling, Van den Berg lives in the Nijmegen Benedenstad. He keeps a blog at www.wanderlustdoc.com.

Globetrotter Floris van den Berg (33) is GP and expedition doctor. He studied Medicine in Nijmegen from 2001 to 2009. During that time he took photographs for ANS. When he is not travelling, Van den Berg lives in the Nijmegen Benedenstad. He keeps a blog at www.wanderlustdoc.com.

What character traits do you need to survive on Concordia?

‘First of all you have to be able to self-reflect. There will be times when you feel unhappy, but you have to be able to admit this to yourself. Some people constantly project their frustrations on the station leader – as if it’s all his fault. And you have to have a positive attitude. If a generator breaks down, you have to fix it yourself. There’s nobody to come and fix it for you. When you come here, you leave your well-ordered life behind. It doesn’t work if you stress out every time something breaks.’

New faces

Over the past year Van den Berg has left the station once to travel five kilometres to meet a land transport. As a rule, he does not go further than one or two kilometres – to the end of the runway. ‘Even then I take the scooter. You quickly run out of breath walking about here because the air is so thin.’

Today Van den Berg went outside for a while, to help carry provisions. For a week now planes have been able to land at Concordia again. This period lasts three months. The remaining nine months the extreme cold and darkness make it impossible to reach Concordia. ‘If you don’t catch the last summer flight you know for a fact that you’ll be stuck here for nine months. No matter what happens.’

The planes bring new faces and stories. This is really nice, admits Van den Berg, after nine months spent with the same group of people. The change is more than welcome. And the planes bring fresh fruit and vegetables. Van den Berg could not believe his luck on the day he got to bite into two fresh avocados. At the top of his wish list now: mangos. For the past months, the menu has consisted of frozen and canned food.

What do you do when you’re done with your work?

‘I have a lot of free time here. I don’t have to go shopping, I don’t have to cook, and I don’t have to visit friends on their birthdays. This leaves you with a lot of time on your hands. I spend this time reading and watching series. I also thought it was a good opportunity to learn a new language, so I got started on Russian.’

You are going home in seven weeks. Are you looking forward to it?

‘Yes, I’m really looking forward to it. Since planes can land here again now the first crew members are already leaving. I’m jealous of them. But on the other hand I’ve still got enough to do. I have to hand over my work and complete some experiments.

When I get home, first of all I want to spend a few weeks with my girlfriend. I’m looking forward to simple things, like grocery shopping. After a few weeks’ leave I’ll start working as a GP again. I’m a real freelance doctor so I spend a lot of time away from home. Next year I’m going to Siberia as an expedition doctor.’

In an earlier interview you said that you might want to become an astronaut. Do you still want to?

‘Maybe. I enjoy working as a researcher in such extreme environments. But it’s important to have a group of social people around you. For a future mission to Mars I would have to be away from home for two and a half years. That’s a really long time. Also for the people you leave behind. I asked my girlfriend whether she might consider joining me, but she wasn’t very enthusiastic.’

You can find more stories about cold in the newest Vox (in both Dutch and English).