This is how Heino Falcke experienced the presentation of his breakthrough

-

Heino Falcke. Foto's: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Heino Falcke. Foto's: Erik van 't Hullenaar

After 20 years, Heino Falcke’s dream finally came true: on Wednesday he presented the first image of a black hole. Vox spent two days with the religious astronomer, travelling with him from Frechen to Brussels. ‘I have prepared myself as well as possible for this moment, but what happens now is in God’s hands.’

Tuesday, April 9

8.15 am. A thick layer of fog covers the town of Frechen, just outside Cologne. The roads to the city are becoming congested with traffic, but the residential area is quiet and peaceful. ‘You are early!’ says Falcke when he opens the door of the former miner’s cottage.

The professor has had a night with little sleep and still has to send a few e-mails.

Tomorrow, the whole world will be watching the presentation of the first image of a black hole. For weeks, the scientists in his research group have been holding discussions via email with each other and with the European Commission. ‘The Commission is not accustomed to holding a press conference with scientists,’ says Falcke. ‘The plans for the press conference are changing, and we have less and less time to tell our story.’

Almost 200 researchers are involved in the project worldwide. ‘Each and every of them has done important work. I would like to give them lot of attention tomorrow, but there is not enough time.’

Falcke closes his laptop, ties his shoelaces and rolls his suitcase outside. He is taking two of everything to Brussels: two suits, two shirts, and even two ties. ‘Actually, I’d rather not wear a tie.’

Falcke closes his laptop, ties his shoelaces and rolls his suitcase outside. He is taking two of everything to Brussels: two suits, two shirts, and even two ties. ‘Actually, I’d rather not wear a tie.’

Falcke’s wife Dagmar has already left for work. She is the principal of a local primary school. His mother-in-law, who lives below him, is still at home. ‘Tschüss, viel Glück Morgen,’ [Bye, good luck tomorrow.] she calls out before he gets into the car.

8.45 am. We drive him to the Cologne Hauptbahnhof train station. In the busy morning rush hour, the professor does not trust our GPS and prefers to give directions himself. ‘Second Ausfahrt. How do you say that in Dutch? Oh yes, afrit (exit). Yes, I know the literal translation into Dutch means funeral,’ he jokes.

Driving along the Rheinufer, we enter Cologne, which is Falcke’s hometown and for him is still the most beautiful place in the world. The Falcke family has lived here for three hundred years, and he has no plans to move either. ‘I chose to work in Nijmegen so I can continue to live here.’

9.30 am. On platform 5, Falcke meets his colleagues Eduardo, Anton and Luciano, who will also speak at the press conference.

Heino uses the first part of the train ride to prepare his talk, and then the four men meet in the compartment between two train cars as the train travels between Liège and Brussels. ‘It’s nice and quiet there.’

11.30 am. A brief moment of panic. On arrival in Brussels South, Heino’s mobile phone loses the signal. ‘Problems with the Belgian network,’ he grumbles. ‘It will be a disaster if it doesn’t work today and tomorrow.’ After getting on the metro, Falcke continues to struggle with his phone. Only when we are above ground does the device start working again. ‘I survived the first crisis,’ Heino jokes.

Heino’s hotel is adjacent to the Berlaymont building, the headquarters of European Commission, where the press conference will take place tomorrow. Before checking in, he quickly takes a few pictures of the building. ‘We arrived …’ appears shortly afterwards along with the photos on his personal Twitter page.

In the run-up to the press conference, he has acquired 500 new followers. The tweets for tomorrow are already planned. ‘Right down to the minute.’

1.15 pm. On the way to the headquarters of the European Research Council on the Rogierplein, the astronomers joke about the Brexit summit that will also take place tomorrow across the street from the ERC. ‘Maybe we should invite Merkel to our press conference? Or Rutte [the Dutch prime minister], who likes to stand in the spotlight at such events. Then we would get even more attention for our announcement,’ suggests Falcke.

Eduardo Ros, from the Max-Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, doesn’t think it’s a good idea. ‘Then the politicians will walk away with all the attention once again. No, tomorrow it’s all up to the scientists.’

1.30 pm. In a somewhat tatty grill restaurant the astronomers have a quick lunch, but not before Falcke has silently given thanks.

2.00 pm. The serious work begins. A training session for the press conference is being held at the headquarters of the European Research Council, the financier of the megaproject. About 25 people are sitting together in a meeting room on the ground floor of a high-rise apartment block. Besides the scientists, the participants include EU employees who are fiddling with their mobile phones and occasionally pacing back and forth nervously.

John Holland, an American who work previously for CBS News and CNBC, leads the session with a firm hand. ‘You have the chance to tell your story to the whole world tomorrow, so don’t mess it up. Remember that is a press conference, not a 90-minte panel discussion. So avoid difficult words. For example, half the world has never heard the term paradigm shift.’

According to the latest plans, the five scientists who will take the floor tomorrow will each have only three minutes to speak. Just a week ago, they expected five minutes. ‘Will the EU Commissioner for Science also have less speaking time?’ Heino asks.

4.10 pm. Katharina Konigstein, who has been Falcke’s management assistant for a year and half, follows the session but also scans the requests for interviews that continue to come in via email.

Without Katharina, the trip to Brussels would be complete chaos, Falcke told us. ‘That is nice to hear,’ says Konigstein.

Although she is also German, Falcke and Konigstein always speak Dutch with each other. ‘When he talks about astronomy, his Dutch is very good. But if he wants to tell you what he did last weekend, sometimes he has to search for a word.’

4.20 pm. Now it’s time to practice the press conference. Because the image of the black hole is strictly embargoed, the fifteen cameras in the room have to be put away.

‘We are looking into space’ are the first words of Falcke’s talk. As he speaks, a film plays in the background that starts with a starry sky and ends with the world premier that that will be presented tomorrow: the first image of a black hole.

During the 50-second simulation, he has difficulty saying everything he wants, so he talks faster. ‘You need to slow down a little bit,’ Holland advises him.

5.35 pm. To practice the round of questions at the end of the press conference, Konigstein and EU staff ask some tough questions.

‘Your project cost European taxpayers millions of euros. What do they get in return?’

‘I was hoping for a milestone that would reduce climate change or eliminate child poverty, but will we only see an image of a black hole?’

‘How will Brexit affect this type of scientific project?’

The answers given by the speakers are then discussed in the group.

6.40 pm. The energy has started to run out. Falcke thinks they have done enough. ‘If everyone practices their talk in front of the mirror tonight, we’ll be fine.’

Holland has the last word. ‘I can’t say it enough: have fun tomorrow!’

7.20 pm. After a busy day in sterile conference rooms, Falcke wants to relax with the other astronomers.

‘Three topic are prohibited while we are eating,’ says Falcke as they enter a flexitarian restaurant next to the Royal Flemish Theatre, ‘the Event Horizon Telescope, black holes and Brexit.’

Now that the scientists are together, the atmosphere is more relaxed. No mention is made of the Brexit, but the other two topics are harder to avoid.

10.00 pm. ‘Let’s get some fresh air.’

Together with Eduardo Ros, Falcke walks from the restaurant to the hotel, from downtown Brussels to uptown.

10.35 pm. Heino rehearses his talk a few times while pacing the carpet in his hotel room.

Tomorrow morning he wants to isolate himself. ‘I have prepared myself as well as possible for this moment, but what happens now is in God’s hands. At such times, I think it’s important to trust Him. If it goes wrong, then I will accept that. But until the press conference, it’s up to me. I have to grit my teeth a bit longer.’

Wednesday, April 10

8.00 am. After another short night – five hours of sleep – Heino is having breakfast with Eduardo Ros and Monika Moscibrodzka, the other astronomer at Radboud University who will soon be addressing the world.

10.00 am. The astronomers work on their plans for the press conference for another two hours.

12.05 pm. Luciano Rezzolla from Goethe University in Frankfurt orders a light lunch in the sandwich shop next to the hotel. ‘We’ve all turned off our phones,’ he says. ‘It is lovely to be away from the outside world for a while.’

12.45 pm. Dressed in suits, the five scientists gather in the hotel lobby. Somewhat against his will, Falcke is wearing a tie.

1.15 pm. Five EU employees lead the astronomers through the room where the press conference will take place. The plans for the press conference are being changed right up to the last minute.

2.15 pm. Journalists who had already picked out a spot are asked to leave the press room temporarily: a spokesperson wants to test the slides one last time.

2.57 pm. The tension in the European Commission headquarters is tangible. In addition to 75 journalists from all over the world, many Eurocrats and #EHTBlackHole staff are in the room.

When the astronomers walk to their seats on the stage, you can hear a pin drop.

3.00 pm. Le moment suprême.

‘Today we are announcing a major breakthrough for humanity,’ says Carlos Moedas, European Commissioner for Science. ‘We are going to present an image of a phenomenon that one person dreamed of a century ago: Albert Einstein.’

Next to him, Falcke stares at the floor, hands folded.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, Professor Heino Falcke will soon reveal the image that we have been waiting for.’

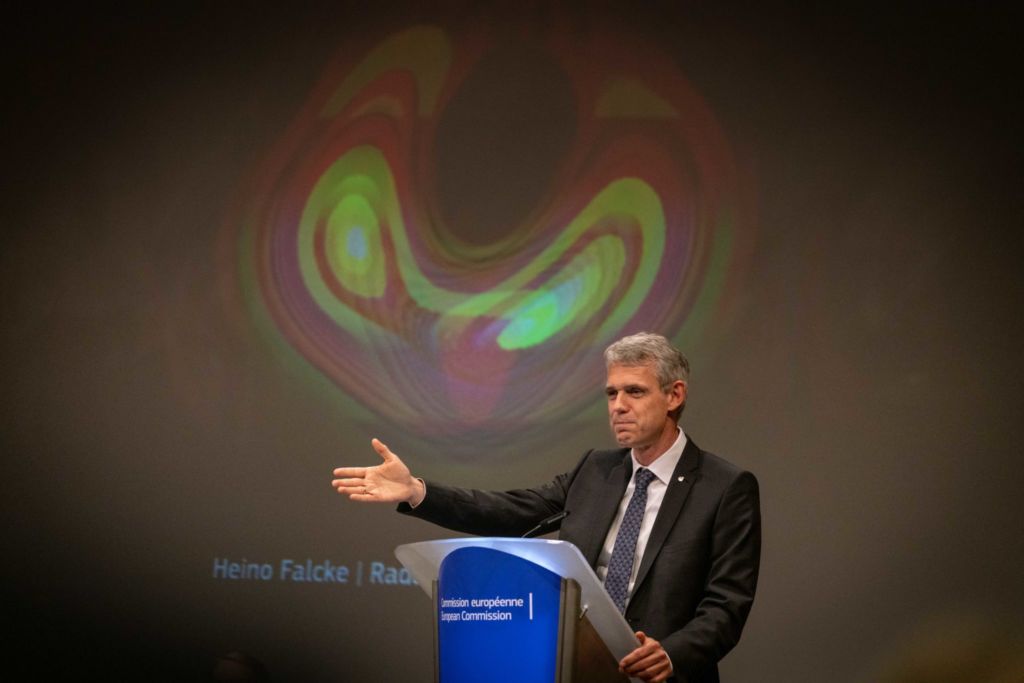

Falcke stands up. Because it takes a while for the film to begin, Heino introduces the four scientists next to him: Monica, Luciano, Eduardo and Anton. While holding onto the lectern with his left hand, Falcke thanks the other team members.

The lights are dimmed, the film starts.

‘We are looking into space’ are the first words of Falcke’s talk.

Then, a slight slip of the tongue.

‘Towards a giant galaxy, 500 billion light years – eh – 500 billion kilometres away from us.’

He recovers quickly, and the rest of the talk goes smoothly.

‘I never believed this black hole was as big as people said. Until we saw … that.’

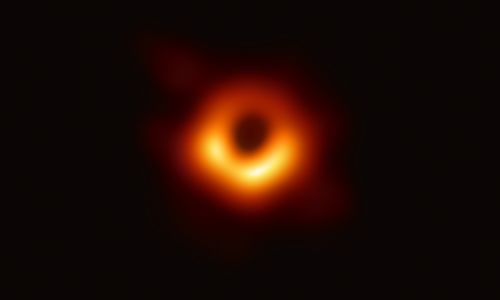

The black spot now appears behind Falcke, surround by a halo of bright yellow radiation.

‘This is the nucleus of the galaxy M87 and this is the first ever image of a black hole.’

He repeats the last sentence in German, Dutch and French.

After he has given the microphone to Luciano Rezzolla, Falcke leans back, legs crossed. Occasionally he smiles at what a colleague says.

3.29 pm. During the Q&A session, no one asks the trough questions that were practiced yesterday.

3.50 pm. After the press conference, Falcke gazes into the room with shining eyes, but not for long. Friends, journalists and colleagues from the Event Horizon Telescope: everyone wants to shake hands with him.

4.30 pm. A small reception is held next to the press room. With a glass of wine in her hand, Moscibrodzka relaxes after speaking to the whole world. ‘The last 24 hours I lived on adrenaline and water,’ jokes the Polish astronomer.

In the meantime, Heino gives interview after interview. Sometimes in Dutch, then in German or English. When an interview threatens to run over time, Konigstein urges the journalist to hurry.

‘I haven’t had any time to call or text anyone,’ Falcke says. ‘Not even my wife. Hopefully I can do that soon.’

5.30 pm. Between two interviews, Falcke analyses his own performance. ‘I wasn’t very sharp, but I did well enough. Everything has come together nicely. I am very happy, especially because it is over now at last. I also give thanks to Our Lord.’

According to Falcke, enjoyment is possible only when you look back on something. ‘But I am not someone who looks back. There is a beautiful Bible text about that. No man, having put his hand to the plough, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God. You must leave the past behind and look forward. I try to do that.’

7.29 pm. ’Thank you for your enthusiasm and support,’ Heino tweets. ‘This was a nerve-racking ride for all of us – from observation to publication. We can finally share this precious image with the whole world. That is where it belongs.’

Falcke has acquired another 1,407 followers in one day.

11.59 pm. The professor will stay another night in Brussels: tomorrow he will give a lecture as part of the centenary conference of the International Astronomical Union. This will be followed by several lectures at Cambridge and in the Netherlands. ‘I don’t know yet what I’m going to talk about.’

Falcke will take a week off after Easter to go to a Christian conference in Sauerland attended by thousands of people. ‘It’s not a holiday as such, but it is something I look forward to. And who knows, maybe I’ll give a brief talk.’

On Wednesday, a team astronomers led by Heino Falcke presented the first image ever made of a black hole. Read here what three of his colleagues say about Falcke. Robbert Dijkgraaf called the image a ‘crucial breakthrough‘.