Virologist Marc Van Ranst confronts conspiracy theories head on: ‘I’m not an action hero’

-

Marc van Ranst. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Marc van Ranst. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Marc Van Ranst rarely allows himself to be led by fear. Even from a safehouse, the Low Countries’ best-known virologist still confronts spreaders of conspiracies and fake news. In October, he is due to receive an honorary doctorate from Radboud University.

There is such a thing as coincidence, as Marc Van Ranst learned in June last year. Within a span of 24 hours, he heard from three Dutch universities that they were awarding him an honorary doctorate. ‘My first response was: they must have agreed it among themselves,’ says 57-year-old Van Ranst in the somewhat sterile lobby of the REGA Institute, the Leuven university building where he works. ‘But it turned out not to be the case. Strange, isn’t it?’

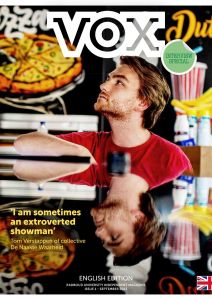

This interview is part of Vox’s interview special, which can be found in the Vox stands on campus, starting next week. The magazine contains interviews with student and NEC player Dirk Proper; researcher Samira Azabar; virologist Marc van Ranst; producer Tom Verstappen; doctor Tanya Bisseling and her student daughter Jasmijn Olde; friar Stefan Ansinger; and influencer Manon van den Bos.

He has in the meantime picked up two of the three honorary doctorates: from the VU Amsterdam and Leiden University. He will receive the third doctorate from Radboud University on 17 October, on the occasion of the University’s centenary celebrations.

And once again, his parents will be sitting in the front row. ‘Of course I’m honoured to be receiving an honorary doctorate,’ says the professor. ‘But my first thought is still: how nice for my parents!’

Father Van Ranst in particular reads anything he can find about his son. ‘He’s like the CIA, the FBI, and Mossad all rolled into one. I’ve told him countless times to stop, but he can’t help it.’ The honorary degrees act as an effective antidote to all the hate mail Van Ranst receives. ‘Finally, my parents can read that not everyone is out to harm me.’

Song Contest

As a virologist at KU Leuven, Marc Van Ranst was one of the Belgian government’s key advisors during the COVID-19 pandemic. He was a member of the Risk Assessment Group, the COVID-19 Scientific Committee and – in the aftermath of the pandemic – the group of 10 experts who were asked to develop an exit strategy. The virologist sat in at about every Belgian table where lockdowns, face masks, and access policies were discussed.

That alone was enough for many anti-vaxxers and other COVID-sceptics to hate him. It didn’t prevent Van Ranst from expressing his outspoken opinions in talk shows and on social media. Twitter is his preferred platform. When he is attacked, or when people talk sheer nonsense, Van Ranst counterattacks.

He even did this from his safehouse, after ex-military officer Jürgen Conings had tried to attack him, with heavy weapons and ammunition in his pocket. ‘People found it very strange that I did that. But I was just sitting there on the sofa with my family and there wasn’t much I could do.’ He starts laughing ‘And then, to make matters worse, the Eurovision Song Contest came on TV. That was just cruel and unusual punishment.’

So yes, at times like that, Van Ranst would take out his phone and check how people on social media were reacting to his involuntary isolation. At some point, Van Ranst requested access to the Telegram group ‘As 1 man behind Jürgen’, where sympathisers of the ex-military officer were gathered online. ‘I find that interesting. The fact that those people really do exist.’ That night, Van Ranst passed the time messaging back and forth with people who would gladly have seen him dead. The last message he sent was ‘Good night warriors!’

‘The media felt I was asking for trouble. As if I was expected to play the victim’

The fact that someone radicalises, becomes confused, and ‘starts doing crazy things’ is not even what surprised Van Ranst most about the affair. It was the fact that a Facebook support group for Conings attracted 50,000 members. ‘Just think about it… there are 50,000 people out there who think it would be a great idea to put a bullet through my head.’ He shrugs as he speaks of it.

Did you expect the social unrest and polarisation to become so intense that you would have to go into hiding with your family?

‘At the beginning of the pandemic, everyone was full of praise for virologists. Society was desperate for information, and we were able to provide it. Those were the honeymoon days. People hung white sheets out of windows in support of health workers. But even back then, in March 2020, I warned that it never ends like that. When they praise you like that, they’re sharpening their knives at the same time. But the fact that a military officer would eventually come after me; clearly there was no way I could predict that.’

Doesn’t that make you feel really unsafe?

‘I find it intriguing more than dangerous. I wanted to read with my own eyes in those groups: what’s going on here? And I responded to what I read, under my own name. The media felt I was asking for trouble. As if I was expected to play the victim and keep quiet.’

Of course, you could say: you were seeking confrontation, even though you were already heavily protected.

‘Why should I silently watch from the side without responding? As in: Don’t feed the beast? Sorry, I don’t believe in that. These people are entitled to my opinion. It’s me they’re talking about, after all.’

Come to think of it, why do you tweet so much? Is it an emotional response, or is there also a strategy behind it?

‘There’s definitely a strategy behind it. People used to send out a press release. During the pandemic, I used Twitter to achieve the same effect. You want to see something distributed, and ten minutes later, you get a call from Belga (Belgium’s largest news agency, Eds.). It happens really quickly. You don’t want to let the people who talk nonsense on Twitter gain too much ground.’

You do often go straight for the jugular, for example in your digital discussions with Willem Engel.

‘There’s no point in saying: “Well, Mr Engel, I don’t agree completely with what you’re saying.” You can also choose not to respond at all. I did that with Engel until he started talking about me. At the same time, he was also getting invited to appear on talk shows. At that point, some people wanted me to debate with him on TV, but that’s something you should never do. Who benefits from something like that? The general public ends up thinking that the truth must lie somewhere in the middle. You wouldn’t enter into debate with someone who says the earth is flat, would you?’

Why do you choose to engage in online discussion then?

‘During the pandemic, there were a lot of so-called scientists who stood up and started criticising the COVID-19 policy. These were often emeriti or people from the US. It’s hard for the general public to assess how much expertise these people have. After all, they do have ‘professor’ in front of their name. In such cases, there’s nothing wrong with saying: this guy trained as a virologist 25 years ago, he has not published a single relevant scientific paper since, but he does invite donations. I think it’s fair to point that out.’

Three questions for Marc

What did you want to become when you were little?

‘An astronaut: after seeing the moon landing as a four-year-old, I was completely captivated by the NASA Apollo programme. As a seven-year-old in 1972, I even tried to telephone Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon. And I did get to talk to someone from NASA in Houston, but the problem was that I neither spoke nor understood English.’

Where did you go this summer?

‘This summer I spent two days at the Efteling. So a trip abroad! The rest of the summer, I spent mostly in Knokke, where I had my first solo exhibition with my digital art works in a gallery.’

Who do you admire?

‘21 July 1969 was a special day. Not only did Apollo 11 land on the moon, but that same day Eddy Merckx won his first of five Tour de France. I promptly became a lifelong fan of this amazing cyclist. Not just because of his unique track record, but mainly because you could see that Merckx was suffering on his bike. I thought that was really inspiring.’

Do you think scientists should speak out more often against fake news?

‘If something is nonsense, you shouldn’t be vague about it. When people write that they’ve become magnetic after being injected with a COVID-19 vaccine, I send a tweet that I’ve been stuck to my fridge for four hours. There are some things you shouldn’t take seriously and it’s good to inject some humour sometimes.’

Don’t you also partly owe your Dutch honorary doctorates to Willem Engel? The lawsuits you won against him haven’t been bad for your reputation.

‘You’d have to ask the universities. But would I have been awarded the honorary doctorates if I’d stayed quietly at the lab and fiddled around with test tubes? Probably not.’

Many of your colleagues are very good when it comes to content, but they tend not express themselves in the media much, if at all.

‘Give them all an honorary doctorate!’

Who are your great examples?

‘You are lucky in the Netherlands to have the best virologist in the world: Ab Osterhaus. Marion Koopmans also certainly deserves an honorary doctorate. And I’d like to bet that a Nobel Prize will soon be awarded to the people who developed the mRNA vaccine (including Katalin Karikó, who received an honorary doctorate from Radboud University last year, Eds.).

‘Being afraid is rarely productive’

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the development of those vaccines. I expect we’ll soon have mRNA vaccines against influenza, RSV, and other infectious diseases.’

Yin and yang

At the age of 12, Marc Van Ranst got his first microscope as a gift, after which he started experimenting in his own private laboratory at his home in Boom. As a 16-year-old, he knocked on the door of the local hospital to ask whether he might be allowed to use their laboratory facilities. Not long after this, he was given the key to the lab. ‘My favourite time at the lab was Saturday evening. I had all the equipment to myself then.’

One of the lessons he learned during that time was that you also need a bit of luck. ‘Those people could also have said: get lost, kid, we don’t have time for this. Times were different then. I would visit pharmacists to collect old chemicals. They had to get rid of them, and they let me take them. There’s no way that would be possible now – you need all kinds of environmental permits for that these days.’

And it’s not just science that Van Ranst is passionate about. His serious hobbies are like yin and yang: stamp collecting and mountaineering. He has climbed Mount Elbrus in Russia, Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, Mont Blanc in France, and Aconcagua in Argentina. All mountains between 4.8 and 7 kilometres high.

Is it in your nature to seek out dangerous situations?

‘No, I seek out the mountains.’

Isn’t it the risks and the excitement that make mountaineering fun?

‘No, no. Why do you climb mountains? Because they are there. When you pitch your tent up there, you’re in the most beautiful hotel there is.’

You climb mountains and don’t shy away from threats. Are you never afraid?

‘It’s true that I’m not easily put off by certain things. But I’m not an action hero or a thrill seeker, if that’s what you think. I don’t let the threats affect my life. When we were allowed out of the safehouse, I simply caught the next train to work. It doesn’t help to be afraid. Yes, I love climbing mountains, and I’m sometimes scared of falling. Definitely. So I make sure I’m careful. But if you’re too scared, you can’t go up that mountain at all. Being afraid is rarely productive.’

You just walk around the Market Square in Leuven, despite all the threats?

‘Yes, I do. But if I go somewhere on an official visit, there’s often some security.’

Exhaustion

With the pandemic behind him, Van Ranst’s life has moved into a calmer phase. ‘My life is one big holiday now, I sometimes say. Too bad that’s not true, but it sounds good.’ He immediately adds: ‘But it’s also not like I had to work in the coal mines for years.’

He is often asked if he doesn’t miss the COVID-19 crisis a bit. ‘People think it must have been a fantastic period for virologists like me.’ But nothing could be further from the truth. ‘There was this constant exhaustion. And it just kept on getting worse. It was draining.’

Looking back now on the government’s intervention, what would you have done differently?

‘If there was to be another outbreak tomorrow, we would do a lot of the same things. We were confronted with exponentially growing curves, and had to act quickly. So should you first have a broad public debate about the measures? No, of course not. Lockdowns are extremely hard, but they also save lives.’

At the end of 2022, the Netherlands was the only European country to go into lockdown one last time. Was that necessary?

‘The problem was that the Netherlands had very few ICU beds. We have twice as many in Belgium, and Germany has twice more still. It enabled us to say: we will get through this wave without people lying in hospital corridors. But you faced the risk of overloading the healthcare system, and people weren’t willing to take that risk. The low number of ICU beds is a policy choice, but it involves risk.’

Is that the Dutch being thrifty?

‘I also argued for more ICU beds in a House of Representatives Committee – at least it could have prevented that last lockdown.

‘That last lockdown was very damaging to public opinion on Covid-19 measures’

But that isn’t going to change I think; people in the Netherlands simply deal with it differently – after all, under normal circumstances, you can get by with so few beds. The fact is that that last lockdown was very damaging to public opinion on COVID-19 measures.’

Are we better prepared for the next pandemic?

‘Many people think we now have a magic recipe for the next pandemic. That we’ll be able to manage it away thanks to smart politicians taking the right measures based on great scientific advice from virologists. That’s not the case, and that’s what I want to warn people about. The only thing we can do – as I said at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic – is turn a massive disaster into a slightly less massive disaster.’

What will be the next virus outbreak?

‘I’m going to give you the same answer that I would have given if you’d asked me in 2019. Probably a weird and unexpected influenza virus. Something avian flu-like perhaps – we saw more and more outbreaks of this among mammals last year. That makes you think: nature is experimenting, and that’s not a good thing.’

‘However, I can’t say anything about the timing. People think we’re fine for now, now that COVID-19 has just passed. That may be true of volcanoes, but unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way with virus outbreaks.’