Why are we sleeping and dreaming? Six insights from science

-

Afbeelding ter illustratie. Foto: Ivan Oboleninov, via Pexels

Afbeelding ter illustratie. Foto: Ivan Oboleninov, via Pexels

A good night’s rest is good for the brain and helps to regulate emotions. At the sleep lab, researchers wake participants in the dead of night to gather data. What follows are six insights on sleep.

Most of us spend the night asleep in bed, although some sleep better than others. A good night’s rest is crucial to our daily performance. At the Donders Institute’s ‘Sleep & Memory Lab’, researchers Sarah Schoch and Nico Adelhöfer study how people sleep and dream, and what this means for their memory and wellbeing. Participants, usually students, spend several nights at the lab. Their heads, faces and bellies are covered in electrodes, which the scientists use to carefully monitor their body (heart, stomach, muscles) and brain signals.

‘To people, it’s like time simply disappeared’

We sleep according to a cycle that consists of several phases. That cycle takes roughly ninety minutes and repeats four to six times over the course of the night. At the start, our muscles and brain become less and less active; we become more relaxed, allowing us to fall asleep. ‘For sleep scientists investigating brainwaves, this so-called N1-phase is the hardest to differentiate from a waking state’, Schoch explains.

After a few minutes, N1 transitions to the light sleeping phase, N2. Across the cycles, this phase accounts for roughly half the night. It is followed by deep sleep (N3), also referred to as slow-wave sleep. ‘This phase differs the most from being awake, which can be seen in the much slower brain signals’, according to Adelhöfer. The sleep cycle ends with REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep. This phase is also called dream sleep because we are much more likely to remember dreams from this phase. In this phase, the eyes move back and forth at a rapid pace, and body muscles are completely relaxed or even paralysed, so that you are unlikely to act out your dreams.

Schoch: ‘At the start of the night, the REM phases are on the shorter side; they can take as little as five or ten minutes, and sometimes they’re even skipped entirely. As the night progresses, the deep sleep phase gets shorter and the stable and REM sleep phases get longer.’

The term ‘deep sleep’ does not always correspond to people’s personal experiences, according to Schoch. ‘Interestingly, new literature seems to point to REM sleep feeling more important to people than deep sleep. The more REM sleep people had, the more they felt like they had gotten enough sleep. I also sometimes notice this with people I wake up in the sleep lab. If they wake from deep sleep, they often feel like they didn’t sleep at all, despite that clearly being the case. To people, it’s like time simply disappeared.’

1. How much sleep do we need?

Donald Trump, Madonna, Bill Clinton, Margaret Thatcher: all claim to only need a few hours of sleep each night. According to sleep researcher Schoch, there are actually some people with a slightly different genetic makeup, allowing them to get by with four or five hours of sleep in (cognitive) tests. ‘However, that is pretty rare.’ There are also people who only feel rested after nine hours. So, while there are differences, for most people seven to eight hours is ideal.

But how do you know how much sleep you need? According to Schoch, it’s important to listen to your body: when do I work best? ‘Try not setting an alarm when you are on vacation and see at what time you wake up.’ Adelhöfer: ‘Some scientists study whether people are night owls or early birds. You can find this out by looking at what you do at those times when you’re in complete control of your sleep schedule. At what time do you go to bed, and at what time do you wake up when you’re free from any obligations?’

2. How important is a good night’s rest?

Having trouble falling asleep, lying awake for hours, or even waking up too early. A lot of people have to deal with sleepless nights. And, as we all know: a bad night of sleep makes it more difficult to get through the day. According to research, good sleep is like spring cleaning for the brain.

‘During deep sleep, toxins that have built up in the brain throughout the waking hours are cleared away,’ explains Adelhöfer. ‘A lack of deep sleep means that the removal of this so-called metabolic waste is much less efficient. This can impair cognitive functions, learning ability and memory; it can also increase the risk of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s.’

‘During deep sleep, toxins are cleared away’

Sleep also appears to play an important role in processing emotions and consolidating information in our memories – more on that later. Both researchers emphasize that sleep is important. ‘When someone’s schedule fills up, sleep is often the first casualty’, according to Schoch. ‘People tend to think “It’s not important; I’ll sleep when I’m dead.” But research has shown that this is not a good idea; we really do need our sleep.’

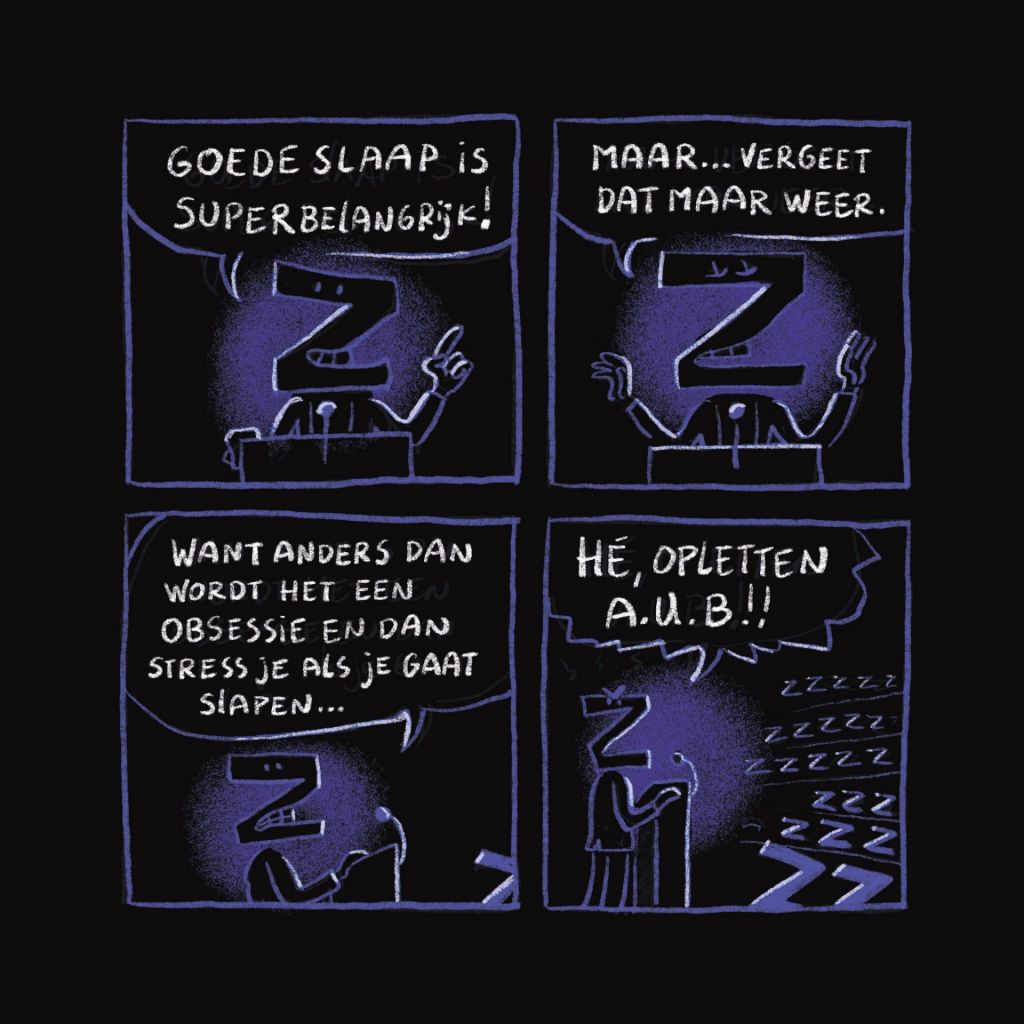

However, they don’t want to put too much pressure on getting enough sleep. ‘People should prioritise sleeping but not worry about it too much. That tends to worsen sleep, rather than improve it.’

So-called ‘smart devices’ like the Fitbit or Smartwatch are very popular at the moment. They can be used to monitor your heart rate, the number of calories burned, or someone’s sleeping pattern. ‘It’s nice that people can track their sleep’, says Schoch, who is also wearing a Fitbit. ‘But at the same time, doctors see people whose sleep has deteriorated because of the active monitoring.’ According to Schoch, these devices can tell you how much you’ve slept overall but are pretty bad at distinguishing between deep and REM sleep. ‘People are starting to worry about a lack of deep sleep, based on inaccurate data. If they sleep worse as a result, this can lead to sleeping problems.’ Additionally, Schoch continues, one or even several sleepless nights don’t have destructive consequences. Not only that, up to a point, humans are a self-regulating system in this area. ‘A lot of research shows that the brain makes up for a lack of sleep during one night with an increase in deep sleep the following night.’

3. Why does everything seem worse at night?

Worrying about an important presentation, mulling over a blunt comment by a friend, wondering about the state of the world. Everything seems worse at night than in the light of day. According to Schoch, research into biorhythms shows that we tend to experience more negative emotions at night than in the morning. ‘We are less enthusiastic or excited, and we get sad, tired, annoyed, or angry much more easily’, Schoch explains. ‘Over the course of the day, there are differences in the number of neurotransmitters (a chemical that can pass signals in the brain between nerve and muscle cells, eds.) that can lead to these emotions.’

Schoch goes on to say that negative emotions can arise due to a lack of sleep at night. In other words: a lack of sleep puts everything in a more negative light; a small problem can quickly seem insurmountable. According to Schoch, this was shown in a study where some of the participants were only allowed five hours of sleep for five nights. ‘When they had to look at images afterwards, it turned out that the participants who got less sleep were much more negative in their interpretations of the images than the well-rested participants.’

‘People were more emotional when viewing images of accidents or dead animals’

‘We think that a lack of REM sleep is a significant cause of heightened emotionality. Studies specifically focused on a lack of REM sleep showed stronger emotional reactivity. For example, people were more emotional when viewing images of accidents or dead animals. Their brains also showed that the areas connected to emotions, such as the amygdala, were more active.’

People who are naturally more emotional, also tend towards sleeplessness, according to Schoch. ‘And that lack of sleep makes them even more emotional. It’s a vicious cycle you can end up in.’

4. Why do we dream?

Something that researchers still know very little about is dreams. That is why, according to Schoch, the honest answer to the question of why we dream is: ‘We don’t know.’ There is simply too little experimental data. ‘Scientists prefer dreaming up pretty hypotheses to collecting factual data’, Schoch jokes. Which is not so strange, given that it is currently impossible to turn someone’s dreams on or off.

The fact that sleep is important for remembering things, also known as memory consolidation, is something that all sleep researchers agree on. Additionally, they suspect that dreams play an important role. Various studies, including the one Schoch is doing, are researching that hypothesis.

‘By dreaming of potentially threatening situations, we can practice them in a safe environment and respond appropriately in the future’

‘In these kinds of studies, we teach participants something before they go to bed. Then we wake them up to see if they dreamt about the things they learned. After that, we look at how well they perform in a test on the learned subject. Sixteen of these studies have been done so far, and combining the results seems to show that dreaming about something you learned does help to improve your memory.’ However, researchers are not sure whether it’s the dreams themselves that lead to improvement. ‘They may just be a reflection of what goes on in our brain’, according to Schoch.

Another possible function of dreams is the processing of emotions. ‘If you encounter something during the day that makes you emotional, that means: this is very relevant, I should store this in my memory’, Schoch says. ‘But if, for example, a month after a spat with a coworker, you’re still as emotional about it as on the day of the event, then that is not conducive to your daily life.’ Research into REM sleep shows that this sleeping phase is very important for blunting the edges of such intense memories.

So, getting enough REM sleep makes someone less emotional. Researchers suspect that dreams about emotional events can have a similar effect. For example, a study into the dream behaviour of people going through divorce showed that those participants who dreamed about their divorce often felt better about it afterwards than those who didn’t, Schoch explains. ‘It’s a very interesting study, but not very controlled: other factors may have affected the outcome.’

Dreams about escaping danger, taking exams you didn’t study for, or getting lost in an unfamiliar place demonstrate that dreams can also be simulations of threatening situations, according to the sleep researchers. ‘That theory has an evolutionary bend. By dreaming of potentially threatening situations, we can practice them in a safe environment and respond appropriately in the future.’

5. What are lucid dreams?

In the Sleep & Memory lab, Nico Adelhöfer studies so-called lucid dreaming. During a lucid dream, the dreamer is aware that they are experiencing a dream. It’s therefore not the same as waking up after a nightmare and realising that none of it was real. ‘In a lucid dream, you realise it’s something your brain made up, not something that’s actually happening. That realisation can allow you to decide what you want to see in your dream. You can make magic happen and do all sorts of special things.’ The moment you realise you’re having a dream, you can start to experiment, according to Adelhöfer. ‘What are the laws of this dream world? Can I read or do math?’

‘Technically, we all become smarter as we sleep’

Lucid dreams are also used in some forms of therapy, but sadly they can’t be done on command. Keeping a dream journal for a few weeks can familiarise you with your dream world, and potentially teach you how to influence it. However, its uncertain nature makes it difficult to measure the effects of lucid dream therapy. Adelhöfer: ‘I think a lot of therapists use it, but the factual results are still under discussion.’

6. Getting smarter while sleeping? That’s possible!

‘Technically, we all become smarter as we sleep’, Schoch says. At the sleep lab, she does a lot of research into memory consolidation: strengthening knowledge in your memory. ‘Of course, we also store knowledge while we’re awake, but sleep appears to be the perfect opportunity for it. Lots of studies have shown that, when comparing learning something and sleeping afterwards versus learning something and staying awake, performance is better in the former situation. We can even see this with babies.’

That is why Schoch has some advice for those students cramming for an exam: go to sleep after studying instead of pulling all-nighters. Reading a complex theory before bed can actually help. ‘Summarise it before you go to sleep; that’s a good strategy. But do make sure that you get enough sleep.’

Translated by Jasper Pesch