You’d better read this article standing up

-

© Bert Beelen

© Bert Beelen

We keep hearing that sitting is unhealthy, that sitting is 'the new smoking'. It also forms a large part of the day for Marit Willemsen. This Vox staff member had her sitting behaviour monitored for a whole week using a special meter and discovered just how bad sitting really is.

I look down at the square box on my thigh. A tiny light flashes every few seconds; I can see it even through my tights. It’s still flashing. So I know I’m sitting now. I get up from the couch, stretch my legs and decide to take a short walk.

A couple of days earlier, I was standing in a research room in the Physiology department of Radboud University with Thijs Eijsvogels. He is an exercise physiologist and is studying the effects of physical exercise on health. Eijsvogels begins by placing a layer of clear adhesive plastic on my leg, followed by the meter, roughly five by three centimetres and wrapped in what Eijsvogels said could best be described as a ‘whole lot of little condoms’. Topped by another layer of plastic. I can’t really feel it and that’s exactly the idea. I can sweat, shower, swim and play sports wearing that thing. It will measure my physical activity for a whole week, and thanks to a kind of smart internal spirit level, it knows whether I am standing, sitting or lying down.

My goal for the week is to discover just how bad desk work actually is for me. As a journalist, I spend a large part of my day seated, as do many students and university staff. In fact, students and schoolchildren sit more than any other working group; eleven hours a day, according to a fact sheet from the Kenniscentrum Sport and the Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM) in 2017. Working Dutch people take second place, with an average of 9.8 hours seated a day.

‘The more you sit, the worse it is for your health,’ says Eijsvogels. That’s hardly surprising. They say that sitting is the new smoking. But just how bad is it?

Premature death

For a long time, scientists paid no attention to sitting. ‘It only started in the last ten years,’ says Eijsvogels. After a decade of research into sitting, the first cautious results are starting to show and they are worrying, to put it mildly.

Sitting leads to higher blood pressure, raised cholesterol, reduced vascular functions and diminished insulin sensitivity which can all have serious consequences. According to a collective American study from 2015, in which the results of 47 studies into sitting were combined, sitting a lot can lead to a myriad of serious illnesses. Anyone who sits a lot – more than eight to ten hours in most of the 47 studies – has 91% more risk of developing diabetes, 14% more risk of cardiovascular diseases and 13% more risk of getting cancer than someone who spends little time sitting. Taken as a whole, a fervent sitter has 24% more chance of dying prematurely, even factoring in possible correlated factors such as smoking or alcohol consumption.

The researcher adds that we should take the increased risks with a pinch of salt. ‘Even if the chances of premature death are 30% higher, for example, the absolute number can still be very low. However, the older you are, the greater the risk of, for example, cancer and consequently death.’ Cancer and cardiovascular diseases are respectively the first and second most common causes of death in the Netherlands. Not only that, but there is a difference between sitting and sitting. Someone sitting at their desk is at least still active mentally. The very worst thing you can do is lie around on the couch watching television. ‘To be honest, I’m not particularly happy with the slogan ‘sitting is the new smoking’,’ adds Eijsvogels. ‘You’ll die faster from smoking a little than you will from sitting a little.’

The denouement

A week goes by. I can’t shake the Big Brother feeling, particularly in the first few days, and the meter burns on my leg if I sit still for too long. But during the course of the week, I forget it’s there. And on the Friday morning, I’m back at the Physiology department. Eijsvogels pulls off the plastic layer of the movement meter in one easy move. He removes the ‘condoms’ from the device and a black box appears.

Postgraduate student Bram van Bakel analyses the data from my device on a laptop, while standing at his high desk. A sticker saying ‘SIT LESS’ in capitals letters is stuck on the back of his computer and on the wall is a kitsch poster of a mouse with the word exercise in an elegant font. Clearly, the researchers take it seriously.

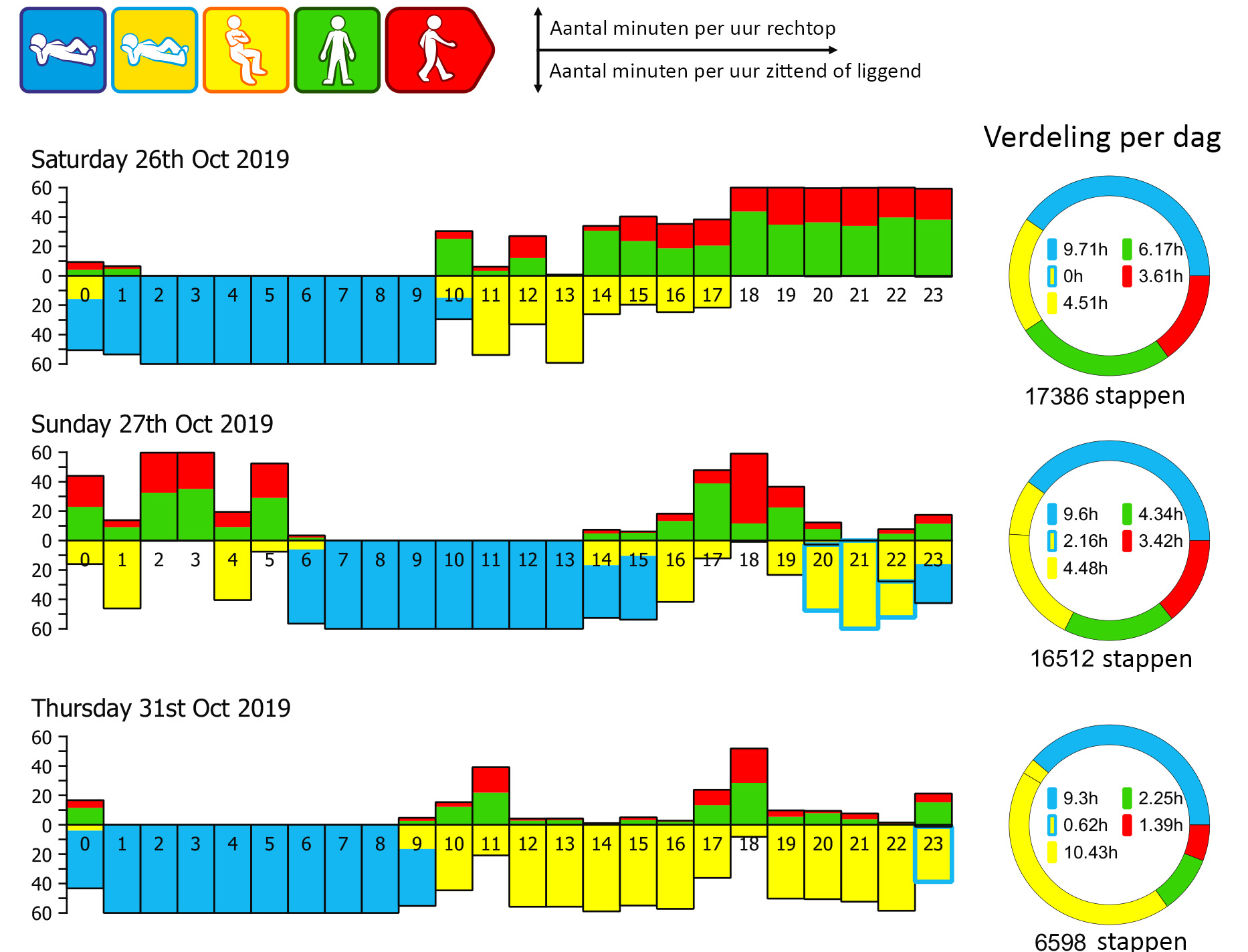

After the data has been uploaded from the device, a number of graphs with colours appear on the screen. Red means I moved or walked, green means I stood, yellow means sitting and there are blue areas for when I was sleeping. I can view my sitting behaviour per day and even per hour.

Eijsvogels and Van Bakel start with the good news. My results are average. ‘And your yellow areas are quite broken up,’ say Eijsvogels. In the meantime, I am looking with satisfaction at the green and red areas on the screen. On Saturday, my first day with the meter, I worked in a restaurant in the evening (my other job), after which I went out on the town with colleagues and I didn’t get to bed till six in the morning. And on Monday, I went to my weekly kick-boxing class. It raises my average nicely. And I can see how I cycled home every evening, walked to do my shopping and cooked.

But then Eijsvogels dampens my optimism. ‘You’re focusing on movement. But if you look at your sitting behaviour, there’s a lot of room for improvement.’ I can see that as the week goes on, and I become less aware of the device, it seems as though I make less of an effort to even get up out of a chair. Thursday really takes the biscuit. The deadly combination of a deadline for work, lunch at my desk and skipping a planned evening of sport resulted in sitting for almost eleven hours.

Still, I do play sports. Doesn’t that compensate for my sitting behaviour? ‘Only if you exercise more than seven hours a week does it no longer matter for how long you sit,’ explains Eijsvogels. The physiologist shows me an overview study from 2016, with data of more than a million people, which looked at the extent to which exercise compensated for sitting. Unsurprisingly, more sport turned out to be better for the life expectancy, but sitting behaviour still had a significant influence as well. The study divided people into groups, based on their sports behaviour (in this context, sport means moderate to intensive exercise, such as power walking or cycling).

I am in the group which exercises between one and three hours a week, and I sit for more than eight hours a day. According to the research, my chances of dying prematurely are consequently 30% higher than those of people who exercise for seven hours a week. That risk is as great as that of someone who barely exercises but who sits for less than four hours. If I were to sit for less than four hours, my chances of dying prematurely would be only 10% higher than those of the healthiest group.

On a mission to sit less

How can I do better, when sitting is such a large part of my work? ‘I never take the lift to my workstation on the third floor,’ says Eijsvogels. ‘And I always stand in the train from my home in Cuijk. If my room mate asks if I want him to get coffee for me, I always say that I’ll get it myself.’ And then there are standing desks, an effective way of tackling sitting behaviour during study or work. Everyone in the Physiology department stands during their meetings. ‘Research shows that standing desks work,’ says Eijsvogels. ‘The question is, for how long’. You have to adjust the desk yourself. ‘There are apps which freeze your screen every half-hour, for example, to force you to take a short walk or raise your desk to standing height,’ says Eijsvogels.

The most important tip that Eijsvogels gives me is not to sit for too long at one time. After sitting for an hour, your body goes into a kind of resting mode, your metabolism changes,’ he says. ‘You want to keep that fire always burning. More and more studies show that getting up and walking around every thirty minutes prevents you from going into that mode.’

‘After sitting for an hour, your body goes into resting mode’

If society’s sitting problem is so clear, why are there still no national anti-sitting campaigns, I wonder? Eisjvogels says it’s because research into sitting is relatively new and the proof is – compared to research into exercise – weak. Add to that the fact that sitting is, in fact, the norm. Almost every time Eijsvogels is standing in an empty train, there will be a conductor who tells him to pick a seat, any seat. The temptation to just collapse into a seat is strong.

I still feel that temptation, but it’s counteracted by the aftereffects of that meter. The device may no longer be with me, but days after I gave it back, I’m still not as comfortable on my chair as I used to be. And I hope it stays like that.