Young historians discover largest slave traders of Amsterdam

-

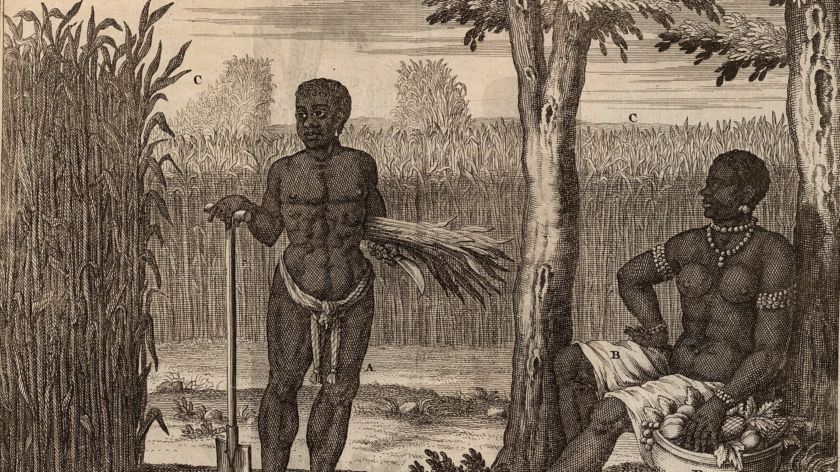

Man en vrouw, tot slaaf gemaakten in Suriname, 1718. Uit J. D. Herlein, Beschryvinge van de volk-plantinge Zuriname, via slaveryimages.org

Man en vrouw, tot slaaf gemaakten in Suriname, 1718. Uit J. D. Herlein, Beschryvinge van de volk-plantinge Zuriname, via slaveryimages.org

Two young historians have found a remarkable document in the Amsterdam city archives: a travel journal that describes life on a slave ship. The discovery has led to them writing a book on the largest slave traders of Amsterdam, whose names were unknown until now. Author and Radboud promovenda Jessica den Oudsten: ‘This is an important story to tell.’

In the summer of 2020, historians Ramona Negrón (25, Leiden University) and Jessica den Oudsten (26, Radboud University) came upon a notable document. Between kilometres of notarial deeds in the Amsterdam city archive they found a travel journal of slave ship ‘t Gezegende Suikerriet (The Blessed Sugarcane). A very important find, according to Den Oudsten, because there is very little known about life on a slave ship.

In the journal, the crew of the ship talk in great detail about their journey. It paints a grim picture of daily life on the ship, where abuses were an everyday affair. Negrón and Den Oudsten were gripped by the papers. ‘We knew immediately that we had to do something with this. It’s a very intense story, but because we know so little about it, it is a very important one to tell.’

Forty Years

The notarial deeds not only show what the enslaved had to endure, but they also reveal who was responsible. Negrón and Den Oudsten, who were finishing their MA in History at the time, discovered that ‘t Gezegend Suikerriet belonged to the biggest slave traders in Amsterdam, two men whose names were unknown until then. They shipped between 11000 and 13000 slaves to the other side of the Atlantic.

Jochem Matthijs and Coenraad Smitt managed a third of the Amsterdam slave trade.

Their names were Jochem Matthijs and Coenraad Smitt, a father and son duo with German roots. For forty years, they sent eight different slave ships between Amsterdam and the West-African coast, followed by Suriname.

Conflict

In their book De grootste slavenhandelaren van Amsterdam (The biggest slave traders in Amsterdam), Negrón and Den Oudtsen describe the duo’s methods. Jochem Matthijs Smitt came to Amsterdam around 1720. At that time, the slave trade was off-limits to private individuals; the Dutch West-India Company (WIC) held a monopoly. Smitt started a merchant firm and built up a network of plantation owners in Suriname.

According to Den Oudsten, this explains how Jochem Matthijs Smitt and his son could become the biggest slave traders in Amsterdam in the decades following the WIC’s loss of monopoly. ‘They already had the ships, crew, and trade network. Other private slave traders tried it once or twice as an experiment but gave up because of the significant financial risks. The second biggest slave traders organised six different shipments; Jochem Matthijs and Coenraad Smitt organised forty-two.

‘Death meant fewer profits for Jochem Matthijs Smitt’

During one of those shipments, the journey of 1743 that Negrón and Den Oudsten’s book focuses on, a lot of things went wrong. The first captain drowned before the African coast, and the second turned out to be a drunkard who misbehaved constantly. During the voyage he ordered physical abuse, causing the deaths of several enslaved persons.

That is the reason why the members of the crew had to report about the journey to the notary when they returned to Amsterdam. ‘Slave traders were only concerned with money, and death meant fewer profits for Jochem Matthijs Smitt. When the second captain came to get his wages, the two came into conflict that wound up at a civil court. The notarial deeds are about that conflict.

Children

There is very little to be found about the enslaved themselves in the notarial deeds. ‘Of course, the archive was assembled by colonisers’, Den Oudsten says. ‘To them, it didn’t matter what the enslaved felt or experienced. Based on the mentioned abuse we tried to paint a picture of what happened to them aboard those ships, but we don’t know who they were, how old they were, or where they came from.’

However, Negrón and Den Oudsten did discover that there were likely children aboard. ‘One of the contracts stated that the captain had to buy children and youngsters between the ages of ten and twenty. We don’t know why exactly, but apparently the plantation owners had a lot of demand for younger people. That’s noteworthy because the WIC preferred people between the ages of 15 and 36.

3.6 million names

In the meantime, Negrón and Den Oudsten have both started PhDs in early modern history – Negrón at the University of Leiden, and Den Oudsten at Radboud University. For the past two years, they worked on their PhDs by day, and at night and on the weekends, they worked on the story of Jochem Matthijs and Coenraad Smitt.

The PhD candidates can still quite regularly be found in the Amsterdam city archives, where they assist in digitising and indexing the notarial deeds as data-curators. So far only 10 percent of the archive has been made available digitally, and the index already contains 3.6 million names. According to Den Oudsten this explains why it to so long for Jochem Matthijs and Coenraad Smitt’s names to come to light. ‘For humans it’s impossible to work through that much information by hand, but you only need to type in a name on the computer and you immediately get results.

‘You only need to type in a name on the computer and you immediately get results’

Now the question is what other discoveries lie in wait. ‘The fact that we only now know the names of the biggest slave traders in the Dutch capital, says something about what else is in the archives.’

The book presentation of De grootste slavenhandelaren van Amsterdam, which was published by Walburg Pers on the 23rd of August, will be held on Friday, September 2nd, at 16:00 at the city archive in Amsterdam.

Translated by Jasper Pesch.