Algorithm sheds light on seventeenth-century correspondence of the common man

-

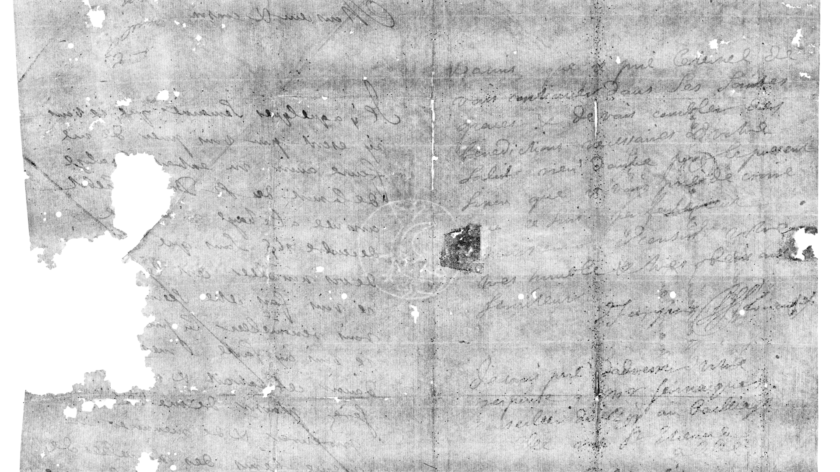

The virtual representation of the letter from Jacques Sennacques from 1697 to his cousin Pierre Le Pers. Photo: Unlocking History Research Group

The virtual representation of the letter from Jacques Sennacques from 1697 to his cousin Pierre Le Pers. Photo: Unlocking History Research Group

Scientists have succeeded in reading a centuries-old, folded letter without breaking the seal. A technological marvel that also sheds more light on the life of common men and women in the seventeenth century. Historian David van der Linden was involved in the research.

In the seventeenth century, which was filled with sabre rattling between France and the Dutch Republic, The Hague was an international city. ‘In addition to parliament, the city was also home to several embassies,’ said historian David van der Linden. ‘And they attracted all sorts of merchants and diplomats. Moreover, the city had a large French community.’

The capital city formed a hub in the international network of written correspondence. And the person who profited the most from this was Simon de Brienne, postmaster in The Hague. He was responsible for bringing in the post from southern countries such as Spain, Portugal and France. The position of postmaster was not one for simple folk: De Brienne had been appointed by no one less than stadtholder Willem III and was very rich.

But not all letters reached their destinations because, for example, the addressee couldn’t be found or refused to pay the postal charges (at that time, the recipient paid). Although such ‘dead letters’ were usually destroyed, De Brienne decided to save them. ‘Because he loved money,’ laughed Van der Linden. ‘He hoped that the addressees would change their minds and decide to collect the post. And sometimes that actually happened.’

It is Simon de Brienne’s collection that plays a central role in a scientific exclusive that Van der Linden and his colleagues presented today via Nature Communications. What makes the collection special is that a large number of the letters – 575 of more than 2600 letters – are still unopened.

What does your exclusive entail?

Van der Linden: ‘By using X-ray microtomography, we were able to read a letter without opening it. It scans the iron particles in the ink and can thus reconstruct the text. Try to imagine how difficult that is: a letter from the seventeenth century wasn’t sent in an envelope but was folded up and sealed. Some parts of the letter consist of 16 layers of paper on top of one another. Via an algorithm, the computer connects the right pieces of text together. This technique can now be applied on a larger scale, so we hope that we’ll be able to read all of the unopened letters.’

International team

The consortium to which Van der Linden belongs and that is researching Simon de Brienne’s collection also consists of scientists from London, Cambridge (Massachusetts, US), Leiden and Utrecht. The technology for the scans was developed at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Financing was made available by the NWO (Dutch Research Council).

Why don’t you just tear open the letters?

‘We approach the letters as a curator; you don’t want to do anything that you can’t repair. If you tear open a letter, you destroy part of the object: the seal, the paper rips. And the letters are also interesting as physical objects: a lot of postal stamp and seal fanatics love things like this.’

What did the scan of the first unopened letter reveal?

‘Of course you hope for something earth-shattering, but it was just a very normal letter from a Jacques Sennacques from Lille to his cousin Pierre Le Pers, a French merchant in The Hague. He asked him to finally post a death certificate of a deceased relative.’

‘When we first read the letter, we thought: is this what we went to so much trouble for? But the letter is interesting because it’s so normal. You don’t find these sorts of everyday requests from common people in an archive. Perhaps Sennacques wanted to secure an inheritance. It sheds light on the life of common people in the seventeenth century.’

You were already able to read the opened letters in the collection. What sort of interesting things did you discover?

‘Especially interesting are the letters from refugees. In 1685 Louis XIV forced the French Huguenots to convert to Catholicism. Some did so, but about 35,000 of them fled, many to the Netherlands. This was a true diaspora in which families were torn apart. That led to heart-breaking situations. For example, a woman in Leiden who wrote to her husband in France that she couldn’t pay the rent or speak the language. She missed her husband so much that she asked him to come and get her. The collection of letters brings these sorts of experiences lets us share these experiences more directly.’

‘It’s sometimes a struggle to decipher the letters’

‘Those who sent letters formed a cross-section of society – not just wealthy ladies and gentlemen, but also many prisoners of war for example. That makes our work more difficult. Sentences are strangely constructed, punctuation is missing. Moreover, they’re written in seventeenth-century French. It’s sometimes a struggle to decipher the letters.’

Why has the collection been saved?

‘First, because De Brienne hoped to earn some money with the letters. Second, he had no children, so he left everything to the orphanage in Delft. He didn’t want his money to be inherited by his relatives in France because they were Catholics. So the letter collection also went to the orphanage, where they sat in a chest until the nineteenth century. Once the orphanage had been nationalised, the collection went to the Post Museum in The Hague (now Beeld en Geluid The Hague), where it has since remained.’

What is going to happen to the letters now?

‘Together with my colleague Rebekah Ahrendt, with whom I spent ten years deciphering the letters, I want to write a book for the general public. About Simon de Brienne, about the stories in the letters and about the seventeenth-century postal system in a European context. It’s about time we did this.’

‘Another entertaining titbit: In the seventeenth century there was a French village on the Loire called La Haye. And La Haye is also French for The Hague. A lot of post meant for that village accidently went to the Netherlands. So by coincidence we know a lot about that obscure little village in the seventeenth century. In the twentieth century the name of the village changed to Descartes because the famous philosopher was born there. I still haven’t visited but, as soon as the lockdown has ended, I hope to be able to enjoy a good glass of wine at a terrace overlooking the Loire.’