As long as the bad guys win

Walter White, Frank Underwood, Jon Snow and Carrie Mathison are popular characters among Nijmegen students, who are dedicated fans of TV shows. Even (or perhaps especially) when the bad guys beat the good guys.

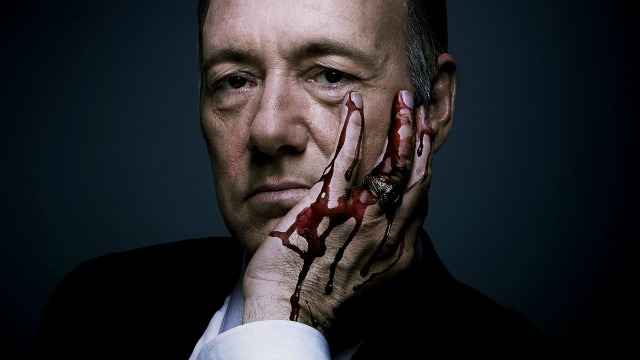

It’s ten past seven on a Tuesday evening. Six young men, most of them political science students, huddle around a small screen to watch a somewhat illegally obtained episode of the political drama series House of Cards. Most of them have already seen the episode, but are happy to watch it again so they can join the discussion afterwards. ‘I never watch regular TV anymore,’ says Bas Bongers. ‘I couldn’t channel surf if I wanted to because I don’t get any TV reception in my room.’ Luc Mevis adds: ‘If I want to watch something that’s not on TV, I’ll make sure to put it on there myself.’

Comments like these are common among today’s youth, who are straying away from conventional broadcasting in lieu of on-demand programming. The TV guide no longer dictates what we watch – we do.

Digital prehistory

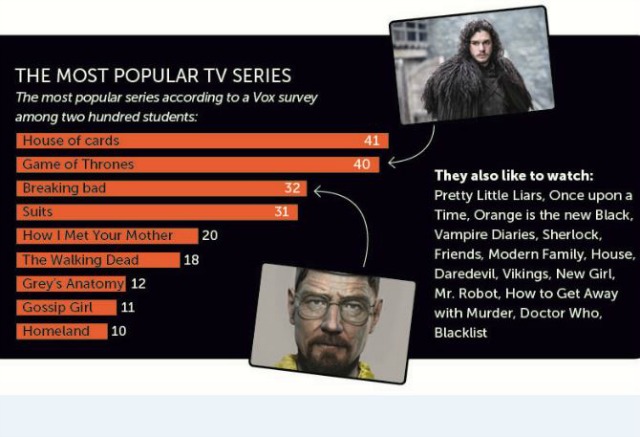

According to Serena Daalmans, a communications researcher at Radboud University who hopes to obtain her PhD on representations of morality in television shows, it’s part of today’s generation. ‘I only turn on the TV to watch the news,’ she says. Vox surveyed the viewing habits of two hundred students and found that 22% watch a television show every day and 43% watch a show at least once a week. Only 18% of respondents claim to (almost) never watch TV series.

Video on demand (VOD) started gaining ground several years ago, as it became easier to download and stream films and series illegally. When Netflix came to the Netherlands two-and-a-half years ago, TV shows enjoyed a considerable boost in popularity and streaming really started to catch on. The Netherlands currently has an estimated 2.5 million Netflix users. Popcorn Time, an illegal streaming alternative to Netflix, has 600,000 permanent users. That’s not including the unknown number of users from other illegal streaming and download providers.

Video on demand (VOD) started gaining ground several years ago, as it became easier to download and stream films and series illegally. When Netflix came to the Netherlands two-and-a-half years ago, TV shows enjoyed a considerable boost in popularity and streaming really started to catch on. The Netherlands currently has an estimated 2.5 million Netflix users. Popcorn Time, an illegal streaming alternative to Netflix, has 600,000 permanent users. That’s not including the unknown number of users from other illegal streaming and download providers.

Nijmegen students navigate the legal and illegal digital highway with ease. Streaming and downloading videos illegally is the most popular way to watch series, according to the Vox survey, which found that 54.5% of students watch shows this way. Of those surveyed, 50.5% also uses Netflix (see text box).

Binge-watching

Users of Netflix and similar streaming video providers tend to be rather fanatical. According to the article ‘Video behaviour of Dutch consumers’, subscribers watch an hour of video content every day on average. This average is much higher in the 18-25 age bracket, which includes most university students.

The high average has been attributed to the phenomenon known as binge-watching, made possible by on-demand video services. Whereas ten years ago fans of the popular TV show Prison Break had to wait a week for the next episode to air, these days fans can watch an entire season in just a few days (or nights). To illustrate: when Netflix released fifteen episodes of the new season of Arrested Development in the summer of 2013, 10% of viewers watched the entire season within 24 hours!

‘Binge-watching has changed the way we watch TV,’ says PhD candidate Daalmans. ‘Watching back-to-back episodes totally immerses you in that fictional world. After a few episodes of House of Cards, a sudden phone call will really make you jump.’

This is a sentiment shared by students who watch the show as well. ‘I try to stay away from series as much as possible out of self-protection,’ says Gijs Swennen with a laugh. ‘Once I start, I can’t stop. I make a cost-benefit analysis to determine whether a show is worth getting into. Because once you start, there’s no way back.’ Bongers has less self-discipline. ‘If I’m in the middle of a season, I have to finish. That’s led to plenty of all-nighters, despite having to get up early in the morning.’

Bad guys

Daalmans is among this evening’s group of happy TV-watchers. She researched the viewing habits for various TV series and, together with her colleagues, spoke with dozens of fans to determine how they arrive at a moral judgment about the main character. She is currently researching an interesting new development in TV-land. ‘Decades of TV research has consistently shown that we like when good things happen to good people on our favourite shows. The good guy has to beat the bad guy. In recent years, however, this pattern is shifting. Main characters are rarely all good or all bad.’

Walter White, the kindly chemistry-teacher-turned-drug-lord in Breaking Bad, is a textbook example. Frank Underwood from House of Cards is another good example as is pretty much the entire cast of Game of Thrones. ‘Main characters are demonstrating increasingly ambivalent behaviour,’ says Daalmans. ‘Morally just main characters are doing bad things, and immoral characters are doing good things. The funny thing is: viewers love it. This goes against everything we thought we knew about the perception of morality on TV. And we have no idea why.’

Diehard fans are taking things one step further. ‘Not only do they refrain from judging bad behaviour, they are justifying said behaviour. We recently interviewed a man who defended Tony Soprano, the mafia boss from The Sopranos. While the man acknowledged that Tony Soprano killed people on the show, he also claimed that the latter didn’t have a choice and that murder was part of the mafia game. He also characterised Tony as a real family man. He only had one mistress, which was nothing compared to his mafia buddies. Halfway through his spiel, the man stopped and said: ‘What am I even saying?’ He seemed a little taken aback by his own comments. This shows the ambivalence of many lead characters and how viewers respond to it.’

The students watching the House of Cards episode also seem to struggle with the morality of their favourite characters. Frank Underwood is a crook in a suit, but the students seem to love him. ‘He speaks directly to the viewer, which I love,’ says Jim Weekers. ‘The way he does it makes him a lovable crook.’ The same can’t be said of Frank’s wife, the equally cold-hearted Claire, although there doesn’t seem to be a good reason for this. When Daalmans suggests that gender may play a role, the students hesitate. ‘Maybe a little…’ Yet another confirmation of Daalmans’ argument: it’s hard to tell the good guys from the bad. But what difference does it make? We’ll watch anyway. / Tim van Ham