Because Nijmegen is safe, even after dark

Sixty students left Brazil this year to spend a year studying in Nijmegen at their government’s expense. This is a record number for Radboud University. What do these South American students hope to find here? Annemarie Haverkamp met with them in Nijmegen and in São Paulo.

(Prefer to read this article in Dutch?)

The city was blanketed in white when Marina Mayor, 23, arrived in her heavy winter coat. With a map in hand, she set out to find the offices of student housing association SSHN to pick up the key to her warm new room. She soon found herself farther and farther away from the civilised world. Feeling desperate, she approached a man who was getting into a car in front of his house. Her breath made little white clouds in the frosty air when she asked him if he knew the way to the SSHN building. She would never have gotten into a car with a complete stranger in her hometown of São Paulo. But this time she agreed when the driver opened the door and offered to drive her there. Grateful, she got in. A few minutes later she found herself in front of the SSHN offices.

Clutching the precious key to her room in her numb hands, she took a taxi to the Hoogeveldt complex. Mayor is just one of the dozens of Brazilians who left their homeland of Brazil to come to Nijmegen in the past three years. This year, Radboud University set a new record when it welcomed sixty Brazilian students. Mayor, an industrial engineering student who has since returned to São Paulo, understands what makes Nijmegen so appealing. “You can cycle everywhere, even at night.” That safety, which started the first day with the stranger in the street, is something most Brazilians can only dream of. We meet in a busy restaurant in the bustling metropolis. Mayor gestures out the window to the pavement outside. “I could never go outside alone at night here.” Robbery, assault and violence are everyday occurrences here.

Elis Assmar (21) from Salvador is spending a year studying Medicine at Raboud University. “Everyone in Brazil knows Science without Borders. I study medicine and always dreamed of going abroad. I’d travelled to Europe before as a tourist, but I wanted to live here and experience the different cultures first-hand. My parents couldn’t afford an exchange programme, so when the opportunity arose, I jumped on it! Classes at Radboud University are smaller than what I’m used to. There’s more interaction with the lecturer, which I like. I also have more time for self-study. At home, in Salvador, I often had classes all day. When I came to Nijmegen in August, I signed up for summer school to learn more about Dutch customs. The weather was great and we went to the city beach, the Waalstrand! Salvador has huge beaches, but watching the sun set over the river was really nice.”

Mayor spent a year in Nijmegen. She came back recently to visit her German boyfriend, who still studies at Radboud University. He plans to move to São Paulo for an internship when he’s done. “We’ll just have to wait and see who moves where.” Her dismissive gesture suggests that things are a little complicated. But anyway, back to Nijmegen. What did her stay in the Netherland teach her? Other than the fact that it’s about thirty degrees colder than where she’s from. “I’ve learned to be flexible. At Hoogeveldt, I lived on a floor with sixteen other people. Until then, the only person I’d ever lived with was my mother in São Paulo. We had Dutch, Indian and Chinese students on our floor, which forces you to adapt.” When she first arrived at the student residence she was all alone, until a housemate asked if she wanted to come along to the Aldi supermarket. She wasn’t familiar with Dutch groceries, but she had to eat. “In the end, you have to figure it out on your own.” To her, studying abroad was enriching. “It really broadened my horizons.”

Out of money

The scholarship programme that made it possible for these Brazilian students to study in the Netherlands is called Science without Borders. President Dilma Rousseff implemented the programme in 2011 with the aim of improving the academic level of the Brazilian population. “The middle class was not sufficiently equipped to fill the vacancies created by the country’s economic growth,” says Wessel Meijer, a policy officer at Radboud University’s International Office. So the president released funds to send the country’s best and brightest science and medical students abroad. There was one condition, however: they had to apply what they learned in Brazil. One of the scholarship’s stipulations requires students to spend at least one year in Brazil after completing the Science without Borders programme. The problem now is that they’ve run out of money. The upward economic trend that this immense South American country had enjoyed suddenly crumbled. The record number of students that took up residence in Radboud’s lecture halls this year will be the last. “It’s a shame,” says Meijer. Getting the Brazilian students over here was no easy task. Meijer and his colleagues trekked halfway around the world two years in a row to promote Radboud University in the warm-blooded country, that requires everyone to take a day off when the national football team plays. “We attended fairs and visited universities to hand out flyers in Portuguese.”

According to Meijer, Nijmegen’s interest in attracting Brazilian exchange students is motivated by its ambition to be an international university. “The idea is to create an international classroom that prompts students to ask each other questions and learn from each other’s different cultural backgrounds.” But the fact that these students are bringing their own money with them certainly helps, admits Meijer. The Science without Borders programme covers all costs, including the teaching costs provided by the faculty and at the same level enjoyed by Dutch students. The arrival of nearly a hundred Brazilian students in three years’ time had a pleasant side effect. “Fourteen of this year’s Master’s students are from Brazil,” Meijer explains. He attributes this to the growing reputation of Radboud University in Brazil. “Students come back and share their stories of Nijmegen.” This may also include students who followed a Science without Borders programme in Nijmegen in the past.

Marina Mayor is happy that she can include a stay in Nijmegen on her CV. She took several management courses to add to the technical skills she acquired during her industrial engineering programme in Brazil. She is currently interning at BASF, a German company in São Paulo, and is convinced that her year abroad helped her land the position. While at Radboud University, she worked on a project for the Donders Institute, took a Dutch language course and learned to speak fluent English. She has no doubt that Science without Borders improved her chances on the job market. And while she may one day consider a career abroad, she’d find it extremely difficult to leave her mother behind.

Mayor makes her way through the busy restaurant and steps outside. She has a night class at Mackenzie University and is using her mother’s car to get there. “It’s much safer,” she says. She can use the car every day but Tuesday, a car-free day imposed by the city. Traffic in this bustling metropolis is so bad that everyone is required to have one car-free day a week. As a result, cycling is on the rise. / Annemarie Haverkamp

Andre Aleotti (18) is from São Paulo and studies Chemistry in Nijmegen. Andre Aleotti thinks it’s crazy that no one at the University of São Paulo speaks English. The chemistry student with Italian roots arrived in Nijmegen in mid-August and finds the international character of Radboud University refreshing. “When I’m in university restaurant De Refter, I’m surrounded by German and Chinese students. All of my classes are in English.” In Brazil, students have to take an English test before they’re accepted to university. Lecturers also have to demonstrate proficiency, although no one uses the language much after that. “Everything is in Portuguese, so we don’t attract many students from abroad.”

Andre Aleotti (18) is from São Paulo and studies Chemistry in Nijmegen. Andre Aleotti thinks it’s crazy that no one at the University of São Paulo speaks English. The chemistry student with Italian roots arrived in Nijmegen in mid-August and finds the international character of Radboud University refreshing. “When I’m in university restaurant De Refter, I’m surrounded by German and Chinese students. All of my classes are in English.” In Brazil, students have to take an English test before they’re accepted to university. Lecturers also have to demonstrate proficiency, although no one uses the language much after that. “Everything is in Portuguese, so we don’t attract many students from abroad.”

Aleotti explains that his parents are relatively well-off and were able to send him to a reputable German school, where he learned English. “I kept up my English skills by watching a lot of American TV shows and by travelling,” he says. In Nijmegen he tries not to spend too much time with other Brazilians. Instead, he plans to use this year to get to know people from different countries. One of the reasons he chose the Netherlands and not, like most Brazilian students, the United States is because of its proximity to other European countries. “I can just hop on my bike and go to Germany!” Nijmegen was his first choice because the university provided him with the best information and patiently answered all of his emails.

Aleotti stirs his tea in the CultuurCafé. Tea is not his preferred drink of choice. “In Brazil we drink coffee, but I’m starting to get used to it.” Another difference he noticed during his time in Nijmegen is the students’ focus. “They seem to be genuinely interested during class. They’re here because they want to be, not because they have to be.” There’s no pressure in Brazil to finish your studies within five years. He thinks this may help to explain the added focus. In terms of academic level, however, he believes the Netherlands and Brazil are on the same line.

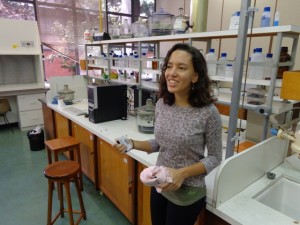

Luiza Pereira (22) is a classmate of Andre Aleotti, who is currently in Nijmegen. She gives us a tour of the Chemistry Faculty at the University of São Paulo. “This is the lab I work in,” says Luiza Pereira as she enters the security code, holds open the door for her Dutch visitor and greets two researchers on the other side of the glass. The chemistry student spends a lot of time in the lab. “In Brazil, it’s normal for students to spend their free time working on their own projects.” She spent a year in Liverpool thanks to the Science without Borders programme and while the lab facilities may have been better there, she has more freedom here.

You need a pass to get through the main door of the faculty. Every visitor has to identify themselves and is registered. The faculty consists of different wings that are connected by a central courtyard. The campus at the biggest university in Brazil, which has 81,000 students, cannot be compared to that of Radboud University. Faculty buildings are much farther apart and the university has other branches across the country. Because many students travel from far, they tend to spend all day on campus.

Pereira leads the way to the faculty’s restaurant. All of the tables are taken. Students can enjoy a hot meal of rice and beans for just fifty cents. “There’s a nicer restaurant for the whole university, but I never go there.” The chemistry canteen is situated above a basement. “People used to throw great parties down there,” Pereira explains. “But a student drowned last year in the river and now they can’t serve alcohol anymore.” Very few students live in student rooms and even fewer live on campus. The library on the first floor is only accessible to those with a pass. All bags have to be stored in a locker. It’s lunchtime and the library is empty – everyone’s downstairs enjoying their rice and beans. In the new lecture hall, complete with digital whiteboard and spacious seats, the quantum mechanics lecturer packs away his things. Pereira explains that it’s normal for students to spend a year abroad. “At least a third of students go abroad.” The only disadvantage: a foreign university on your resume no longer makes you stand out. Moreover, not all Science without Borders students take their studies seriously. Some just use the time to travel. “In Brazil, it’s also known as Tourists without Borders.”