Budget cuts have a big impact on internationals: ‘It feels like watching a car crash in slow motion’

-

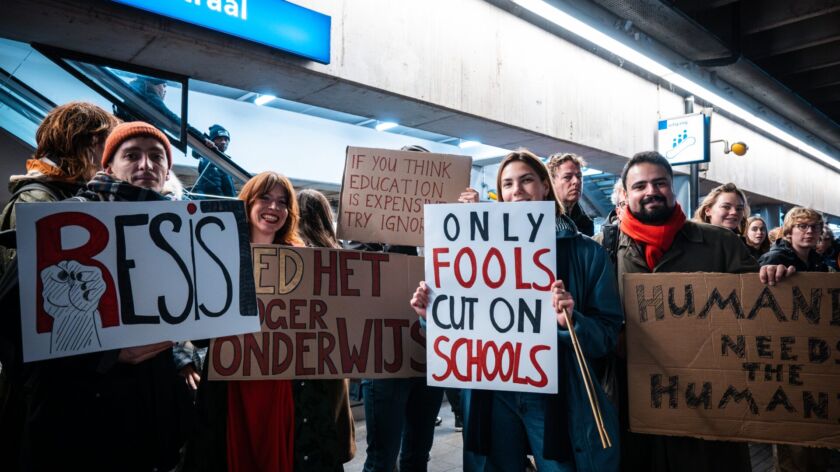

Demonstration against the budget cuts on higher education, last November. Photo: Diede van der Vleuten

Demonstration against the budget cuts on higher education, last November. Photo: Diede van der Vleuten

While the proposed cuts to higher education were partially reversed at the end of last year, there are still significant reductions in funding forecast. These changes will also influence international students and staff members. ‘As an international student I am a bit scared that my options will be smaller in the coming years.’

Aina van Lipzig recently learned that her English taught programme, Comparative European History, will be one of the Radboud studies cut in 2025. ‘We got an email around the beginning of November telling us it had been officially discontinued’, says the 19-year-old German student. ‘I think it’s a really sad decision and I don’t think anyone’s happy with it.’

After negotiations between opposition and coalition parties, the Dutch government decided last December to reduce the higher education funding cutbacks from 2 billion euros to around 1.3 billion euros. This means that more than half of the cuts will be upheld. In addition to financial changes Minister of Education Eppo Bruins wished to de-internationalise Dutch higher education by, for example, making the administrative language at universities Dutch.

While Radboud University has not confirmed whether Van Lipzig’s study was cut due to the policy changes, the university does not fall under the so-called declining area (Krimpregio) that would be exempt from the de-internationalisation efforts. A university spokesperson remains positive: ‘We are still considering how to apply the new policy to various parts of Radboud University, but internationalization is important for our university. Diverse classrooms help our students get a better understanding of topics from different points of views.’

The head of the department of Student Life and International Mobility, Charissa Van Mourik adds: ‘In case we have less incoming degree-seeking students, it is even more important to focus on incoming exchange students to make our classrooms more diverse.’

Uncertain future

Bruins recently stated that the number of international students in the Netherlands will not have to be reduced as much as previously expected, as his budget cuts are likely to be met with the current number of internationals. Nevertheless, students remain uncertain about their future. Van Lipzig says: ‘I also wanted to do a Master’s programme in the Netherlands, but as an international student, I am a bit worried that my options will become more limited in the coming years.’ She and some of her friends attended the protests against the budget cuts on Radboud campus last November.

Not everyone is equally enthusiastic about the protests. South African master student Elona Wheeler (27) is not convinced that protesting will halt the cuts: ‘This government does not seem to listen to protestors. To me it seems that the right-wing parties think that higher education is a kind of enemy and they are trying to cut down on it.’

‘If staying in The Netherlands is going to be an uphill battle and this is only the start of it, how much worse is it going to get?’

For a lot of international students, the future remains unclear. Wheeler says: ‘There seems to be this undercurrent of slight anxiety, a sense of foreboding and trying to do the best that we can without knowing certainly what will happen. It feels a little bit like watching a car crash in slow motion – you are hoping it’s not going to happen but it probably will.’

While Wheeler thinks the effects of the policies will not affect her too much personally, she considers certain right-wing rhetoric, such as Minister of Education Bruins’ statement about international students being responsible for the housing shortage, the biggest issues the country is facing. ‘In South Africa internationals, especially those who contribute to the society through education and in key sectors, are seen positively. But here in the Netherlands internationals are seen as diluting Dutch culture and education by taking jobs/housing and so on. A typical right-wing talking point.’

English friendly country

Wheeler’s observations are supported by the Report on adequate housing by the United Nations in 2024. The report states that the narrative of foreigners being the reason behind societal issues like housing has gained traction in the Netherlands and has been used for political goals.

‘Studying abroad is not something you take lightly’, Wheeler says. She explains: ‘I came to study law in the Netherlands because it is the legal capital of the world and one of the most English friendly countries. But the tuition I have to pay and the fact that I do not have a grant make studying here a financially complicated decision. That is why seeing yourself being talked about and considered unwanted is very sad. I would like to stay in the Netherlands after my studies, but if staying is going to be an uphill battle and this is only the start of it, how much worse is it going to get?’

The master student believes that the benefits of internationalisation in higher education might be overlooked in the debate about budget cuts: ‘Having diverse perspectives coming together in an educational setting provides diverse perspectives and helps to shape the subjects and research areas in a non-Eurocentric way. I believe that de-internationalisation is also affecting Dutch people. Some of them appreciate the English language programmes and purposefully choose them to kickstart an international career.’

Concerned staff members

International staff members are also concerned about the changes. Among them is the Spanish assistant professor Noemi Mena-Montes: ‘I teach on social media, new media and society. How would you teach this sort of topic in Dutch or any other language that is not English? Everything about it is in English already; most things we do online are in English. So, teaching these courses in Dutch would mean a lot of work and reverse translations.’

Mena-Montes adds: ‘I think the question that needs to be asked is what is the benefit of teaching in Dutch in the long run when everything is increasingly in English? This question does not only resonate with her own field of studies, she emphasises, but also with other inherently international programmes and courses.’

‘The biggest question is how we could have a constructive dialogue as a society’

Like students Lipzig and Wheeler, Mena-Montes sees the proposed changes as a step back for Dutch society and higher education: ‘I think most people think the changes will affect the educational level of the universities in the long term. And it’s interesting that the Netherlands is going back on this internationally oriented outlook, especially considering that English skills have given the Dutch and the Netherlands an advantage, not only in the academic world but also in international job markets in general.’

According to her, the current response of protesting the cuts does not resolve the polarisation of society over the issues of de-internationalisation and defunding of higher education either. ‘Protesting is simply reacting to the changes we do not want, but it is only a necessary first step. Most people not in the academic bubble still believe in this narrative of blaming the internationals. The biggest question is how we could have a constructive dialogue as a society. How can we as academics respond and communicate to the general society that our reactions against the budget cuts and de-internationalisation are not coming from a place of privilege, but that they will affect us all in the long run?’