Ode to student friend Robert Regout

Had he lived today, Robert Regout would have been called a student pastor. In 1937, his job description was ‘student moderator’. Although the young priest was immensely popular in Roman Catholic Nijmegen, he was arrested by the Germans in 1940. Seventy-three years later, a commemorative plaque will be unveiled at the site where he died of exhaustion: Dachau concentration camp.

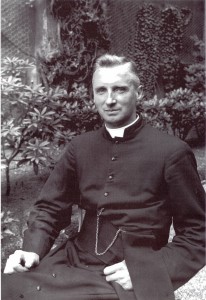

Prisoner 26.750. That was Robert Regout’s designation when he died in concentration camp Dachau in 1942. Two years before, he had been a popular confidential advisor to Nijmegen students. His job, student moderator, was comparable to that of a present-day student pastor. However, in those days nearly all Nijmegen students were Roman Catholics and Regout was therefore a welcome guest in student circles. A few days before his death on 28 December 1942, he wrote, “If Our Lord wants me to ‘sacrifice’ my life, then I will gladly give it, for my faith, for my country and especially for the students and professors of Nijmegen university.”

This love of Nijmegen was reciprocal, and people in the city on the Waal were shocked by his death. Father Regout is remembered as a ‘source of inspiration in student life’. To honour this memory, a commemorative plaque will soon be unveiled in Dachau. Sebastiaan Roes, Professor by special appointment of Notary Law, will personally hand over the work of art in late September. “Near what used to be the barracks is now a memorial site,” he says, “where all the wreaths and plaques for people who died in Dachau can be seen. We asked whether there was a place there for Regout.”

The archive comes home

Why is this friendly priest only now commemorated, 73 years after his death? That is a long story. It begins shortly after the Second World War, when the Russians move the Gestapo archives from Berlin to Moscow as part of their war booty. Among the papers is a file labelled “Robert Regout”. Obviously, the Russians completely ignore it. The Nijmegen records are discovered much later, when a Dutch researcher starts to explore the archive at the beginning of the 21stcentury.

After negotiations conducted by the Dutch government, part of the material is sent to the Catholic Documentation Centre, while documents pertaining to Jesuits are returned to the order. These will be included in the archives of the Dutch Jesuits (in the Huis Berchmanianum grounds on the Houtlaan, next to the university campus). “In 2002, the papers were back in Nijmegen. A group of people then founded theVriendenkring van Robert Regout (‘Friends of Robert Regout’),” says Professor Roes.

Roes was not one of them, since he joined in 2008. Together with the then archivist of the Dutch Jesuits, Marc Lindeijer, the initial Friends examined the letters Regout wrote from Dachau and investigated his mysterious arrest so early in the war. Why were the Gestapo after him? The current archivist, Joep van Gennip, explains. “On 7 June, one month after the German invasion of the Netherlands, Regout wrote an article in the Jesuit journal Studiën, stating that the occupying forces had obligations as well as rights.” Perhaps the Germans wanted to set an example by immediately arresting the priest, who was also Professor by special appointment of International Law. Regout travelled the country to advise mayors, police officials and other authorities on how to deal with the occupying forces. He was also discussing resistance strategies with the universities. On 29 June 1940, the day that the Gestapo knocked on the door of his Molenstraat domicile, he was on the road. Back in Nijmegen, he dutifully gave himself up to the Germans. In hindsight, he should not have done that. “He never got out again,” says archivist Van Gennip.

Regout was first taken to Arnhem prison, where he was in the company of several fellow professors who were eventually released. The Nijmegen priest, however, was transferred to Berlin together with a group of priests, scholars and journalists who were suspected of having contacts with the German Jesuit Friedrich Muckermann, an adversary of national socialism who had been living in hiding in the Netherlands since 1934. According to the archivist, Regout was not part of the Muckermann network, but the Germans may have thought otherwise. “Despite being jailed, Father Regout always remained optimistic,” says Van Gennip. “This is evident from correspondence of cell mates of his.” The surviving letters show that the young priest acted as confidant to his fellow sufferers in prison too. Again, he was a kind of confidential advisor. He was a true pastor, one of his cell mates – who was later released – wrote in a letter of thanks.

Forgotten martyr

In 2002, the Vriendenkring saw to it that a portrait of Robert Regout was placed in the Molenstraatkerk alongside the portrait of Titus Brandsma, the much better-known Nijmegen ‘martyr’. “Regout had more or less been forgotten,” explains Roes, “He had only been a student moderator for a few years and a professor for an even shorter period. His career had only just begun.” Because the archive had been seized by Russia, little remained of him after his death. Once the papers were back, the Friends immediately started on his biography, which was published in 2004.

About Regout’s period in Dachau (July 1941 to December 1942), it states that he probably worked on the transport detail. “This was one of the most dreaded assignments: pulling, loading and unloading carts measuring eight to nine metres in length. The loads – potatoes, coal, salt, machinery as well as dying prisoners and corpses – could weigh up to 8,000 kilos. The prisoners had to pull full carts and offload sacks quickly, while empty carts or empty sacks had to be returned on the double. Cane and boot ensured that these orders were obeyed.”

Later the Professor of International Law worked on the camp plantation. He only broke in April 1942. Hundreds of clergymen were then driven from their barracks and were ordered to stand naked on the Appellplatz. From the biography: “This cruel game was repeated several times on several days. For hours, the prisoners had to march at a gruelling pace around the courtyard and through the streets of the camp, their feet cut up, wearing only wooden sandals, poorly clothed, in silence or singing SS songs when ordered to do so.” When Regout helped a dying Polish priest to his feet one day and asked whether the man could be transferred to the sick bay, a guard banged the Pole’s head against the wall. When the Nijmegen priest asked why, he was kicked so hard in the crotch that he had to go to the sick bay himself.

“He died in December of that year from exhaustion,” says archivist Van Gennip. Although the plan to honour Regout with a plaque had been around for some time in Nijmegen, there were no funds to realise it. There was also no consensus on how it should look. When Nijmegen artist Cor Litjens was commissioned early this year, the job was soon done.

In September, Professor Sebastiaan Roes will drive to Dachau with the twelve-kilo bronze plaque in his boot. There he will witness the hanging of this plaque for Robert Regout. “It will be a low-profile affair,” he says. At one time, there may follow a ceremony. The main thing is that this Nijmegen student friend will no be longer an anonymous Dachau victim. / Annemarie Haverkamp

THE PLAQUE “Met inzet van al zijn krachten het recht en de waarheid te helpen vestigen in deze wereld (‘With all that is in him, helping to establish justice and truth in this world’).” This text is engraved in the bronze plaque dedicated to Robert Regout. It is a sentence taken from the inaugural lecture which the Jesuit professor gave in February 1940. “It’s really a plea,” explains archivist Joep van Gennip, “an appeal to mankind to let justice reign.” Regout was Professor by special appointment of International Law. He had written his doctoral dissertation on the question when war was justified, basing himself on Christian values. “Regout’s appeal is still valid,” says Van Gennip. “Just look at Syria and other places in the world were conflicts rage.” Regout advocated a League of Nations defending the peace instead of promoting the interests of the individual member states.

The bronze plaque was made by Nijmegen artist Cor Litjens. Regout’s effigy is based on his portrait in the Molenstraat church. According to the artist, mildness shines forth from his visage. The portrait is a relief. Using a special technique, Litjens has ensured that the more elevated parts are dark and the depressed parts light. It is usually the other way around, but this enabled him to give the priest a white collar.

Other war heroes of Radboud University Nijmegen

- Titus Brandsma (1881-1942). Titus Brandsma is very well known in Nijmegen, where, inter alia, a community centre and a chapel were named after him. Brandsma was a Carmelite priest and lecturer in Philosophy at Radboud University Nijmegen, which was founded in 1923. He advocated a free press and wrote for regional daily De Gelderlander and other publications. As early as the 1930s, he began to oppose national socialism. In January 1942, he consulted with chief editors and managers of Catholic newspapers to inform them that the bishops had prohibited the publication of NSB advertisements. He was then arrested by the Germans. Brandsma was also interned in Dachau, where he died in 1942, the same year as Robert Regout. In 1985, Pope John Paul II beatified him.

- Bernard Hermesdorf (1894-1978) was Professor of Roman and Old Dutch Law and served as Rector Magnificus of Radboud University from 1942 to 1945. He refused to collaborate with the occupying forces. He resisted their order to supply men for forced labour and the pledge of loyalty which the Germans demanded of Dutch students. Hermesdorf was the only Dutch Rector who did not forward the pledge form to ‘his’ students. Consequently, the Nijmegen university was closed on 11 April 1943. Hermesdorf lived to an advanced age at the home he had designed for himself on Groesbeekseweg, Nijmegen.

- Jan van Hoof (1922-1944) was a scout and student who died at age 22 as a resistance fighter. In 1944, the bridges across the Waal river were fiercely contested. When the Germans tried to blow them up, the charges failed to explode. Some were sabotaged by the Americans, others by Jan van Hoof. He was arrested and shot by the Germans when he tried to show a British armoured car a clear path through the city. There is a monument near the Waal Bridge honouring Van Hoof and other resistance fighters: a man carrying a flag in bronze (by Marius van Beek). A plaque for Van Hoof made by artist Jac Maris is attached to one of the bridge pillars.

The author consulted the biography Robert Regout, Maastricht 1896 – Dachau 1942 (2004, Vriendenkring Robert Regout / Omnia Fausta Publishers) for this article.