‘Restoring the ravaged farmland of Ukraine will cost around 20 billion euros – and that figure is already outdated’

-

Afbeelding ter illustratie. Foto: Tom Fisk via Pexels

Afbeelding ter illustratie. Foto: Tom Fisk via Pexels

Around 20 billion euro is needed to restore Ukraine's war-ravaged farmland, economist Killian McCarthy has calculated. The big question is who will pay for it. ‘The farmers themselves can't. And I fear that agriculture is at the bottom of the Ukrainian government's list.’

Ukraine is nicknamed the bread basket of Europe, a country known for its large-scale grain exports. By way of comparison: Ukraine has more agricultural land than France, Poland and Germany combined. No wonder that, following the Russian invasion in 2022, those exports were widely discussed in the Netherlands too – as well as the possible rise in the price of bread.

But what was rarely mentioned was the impact on poorer countries of the sudden halt in grain production, says Associate Professor and economist Killian McCarthy. With a team of geologists from Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, the Ukrainian Researchers Society and the Kyiv School of Economics, he studied the financial impact of the war on Ukrainian agriculture.

No plan B

‘Western European countries have a plan B to get their food’, McCarthy explains. ‘But countries like Libya, Lebanon or Yemen, where there is already a lot of poverty and famine, don’t. Or look at Egypt, a country of 114 million people. 10 percent of that country’s food comes from Ukraine. Millions of Egyptians now have less to eat.’

‘The number of craters is unprecedented; it takes about 90.000 truckloads of sand to fill them’

In short: grain production must go up. But that is easier said than done. Anyone thinking that the situation will improve once the war is over, will be disappointed. ‘It’s a hopeless task’, says the economist. ‘Naively, I always thought that things would return to normal for farmers once the war was over. But that obviously won’t happen.’

‘Sand was always ‘just sand’ to me. And I assumed that you can just throw it back when you fill a bomb crater’, he continues. ‘But that’s not the case. There needs to be a certain stratification in the soil for fertility. That requires a lot more precision work. And the number of craters is unprecedented; it takes about 90.000 truckloads of sand to fill them.’

‘In other places, however, the ground needs to be tilled because it has been completely flattened by heavy tanks, squeezing out all the air. The soil is so compact in some places that nothing can grow there. But before you can start ploughing, you need to be sure that no explosives have been left behind and that the soil has not been contaminated.’

And that’s not cheap. Checking the land, for example, already costs around 40.000 euro per hectare.

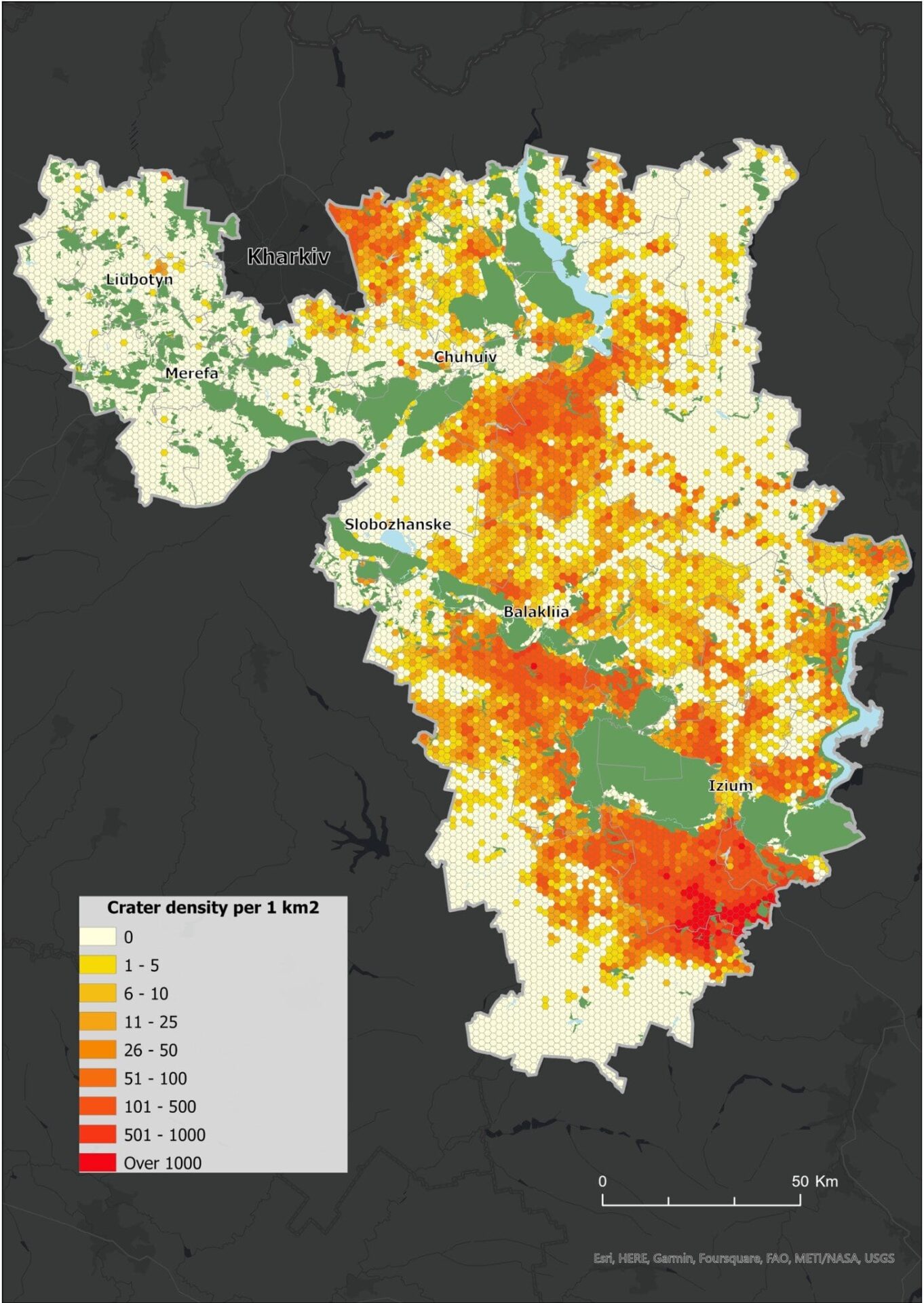

In the Kharkiv oblast (a kind of province) alone, McCarthy and his team estimate the total cost at around 2 billion euro. By comparison: Kharkiv is about the same size as the whole of Belgium. ‘If we assume the same amount of damage in the other oblasts, the total comes to 20 billion euro’, says McCarthy. ‘And that doesn’t even include man hours and transport costs.’

Satellite imagery

To arrive at these amounts, the team of geologists conducted research using satellite imagery and soil samples acquired from fieldwork. They wanted to reveal the physical damage that the war had on agriculture.

McCarthy, originally a strategic economist and by his own admission ’totally ignorant of geology’, became involved in the project through his work at Kyiv School of Economics. ‘They did the hard work. I just studied the reports and tried to put a price tag on it.’

‘Not to mention what might happen when a farmer starts ploughing a field where there may still be explosives…’

The big question is who will foot the bill. ‘Farmers themselves can’t pay. A professor in Ukraine earns about 400 euro a month. So, 40.000 euro per hectare for a farmer is already an abnormally high amount.’

‘The Ukrainian government? They will invest in infrastructure, the health care system and education first’, the Associate Professor continues. ‘Agriculture probably isn’t at the top of the list. Europe or the US? They are increasingly turning off the fundings. Eventually you will see farmers taking risks and using the land anyway, with all the consequences that entails.’

The land is not fertile enough and grain production could only run at half capacity at most, McCarthy explains. Farmers are basically overexploiting the land, because it only makes the soil less fertile over the years. And that is still an ‘optimistic’ scenario. ‘Not to mention what might happen when a farmer starts ploughing a field where there may still be explosives…’

Outdated data

Moreover, the amounts mentioned by the Radboud researcher are already outdated. The team that did the soil research did so back in 2023. ‘Meanwhile, the war hasn’t improved the situation’, he says with a sense of understatement.

‘The saddest thing about the situation is that it is the poorest people who are hit hardest: the farmers in Ukraine itself, the people in countries like Lebanon or Yemen. Eventually, you will see people from those countries fleeing to Europe because of the famine that will break out there.’

‘Politicians in Western Europe and the US are not yet too concerned because it all feels far away. But as soon as it gets closer to home, you will see that stricter anti-migration policies are implemented. Whereas the most sustainable solution is to stop the war and restore the country.’

Which is why it is so important that the war in Ukraine ends quickly, McCarthy stresses again. And that farmers there can return to work on their clean farmland as soon as possible, with help from Western Europe and the US. ‘But if I’m honest, I don’t see that happening anytime soon. All in all, it is a depressing story.’